With so many heart-warming, CSR-led ads winning awards these days, setting a purpose seems to have become almost a prerequisite for launching a big brand campaign.

But many in adland would say these wins are due more to tugging on judges’ heartstrings rather than demonstrating great creativity or solid business results. Or even a sensible purpose in the first place!

This debate came into sharp focus at the Cannes Lions this year, according to a new analysis released by WARC. We dug deep into the entries for this year’s Cannes’ Creative Effectiveness Lions. That’s the category in which entrants must have won a Lion for creativity, but are also able to demonstrate standout effectiveness. With 50% of judges’ marks going on results, and the whole category audited by PwC, the Creative Effectiveness Lions have gained considerable credibility in the industry since their launch in 2011.

We at WARC think so too, having published cases from the category since the beginning. (The complete set is available for subscribers here.) And we launched our analysis at an event in London earlier this month.

While the event covered a lot more data and insights than I’ll write about here (subscribers can read my full report from the event), here are the main points from the brand purpose discussion:

- More and more Creative Effectiveness Lions entries are brand purpose campaigns…

- …but many in the industry – including the Creative Effectiveness jury – are more and more cynical about these campaigns.

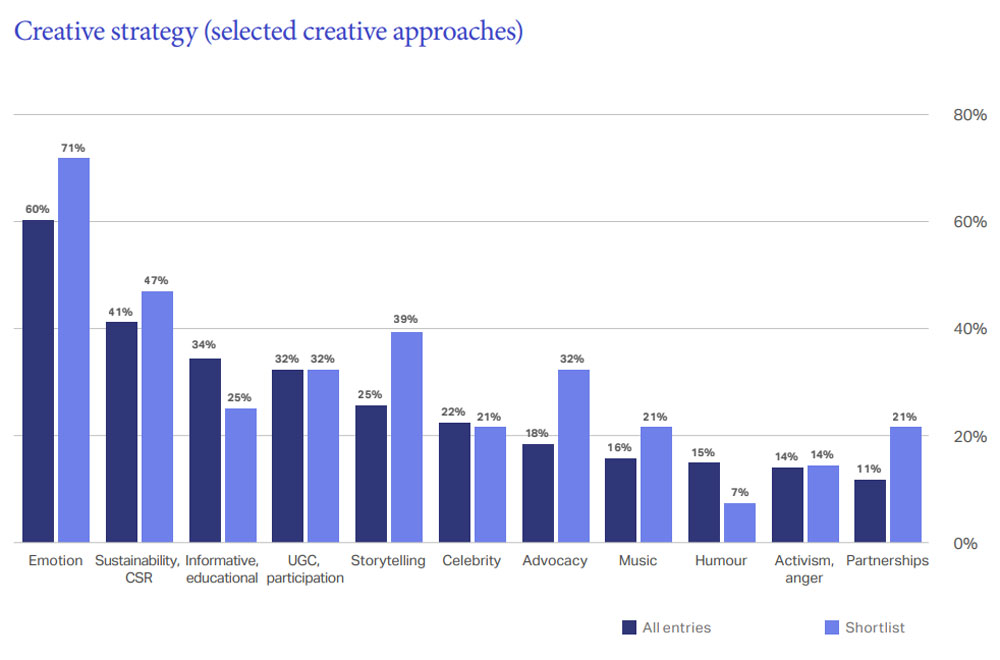

Let me explain. One big trend picked up by WARC’s Cannes analysis is the significant increase of brands using sustainability or CSR as a creative approach.

Source: WARC

Source: WARC

Nearly half (47%) of the shortlist used this approach in 2017, a significant increase from the year before. And, despite the jury’s cynicism, a shortlisted entry was more likely than a non-shortlisted entry to be a CSR campaign. (Also note that emotional campaigns are most likely of all to be shortlisted – the heartstring factor again.)

But members of the jury interviewed by WARC in Cannes felt that brands are being given generic purposes, with a minimal fit with the brand, solely to win awards, rather than drive sales.

“It’s important that brands do lean in to social issues that their communities care about,” Airbnb’s Jonathan Mildenhall, who headed the jury, said. “We were very strict about the cause-related work that we recognised. All of the ones we recognised actually changed laws in the markets they ran in. They had a social objective at their heart, and actually changed society for the better.”

How to set a purpose (if you really want to)

So, what’s a brand to do? Purpose is a popular creative approach. And it’s trendy: there’s a sense that it’s the “right” thing to be doing. But at the same time, the jury’s out on whether it actually works.

Speakers at the WARC event offered different tips on how to navigate the brand purpose issue. Here’s three.

Tip 1: Be strict about definitions

Jane Bloomfield, head of sales and marketing at Kantar Millward Brown, called for more careful definitions for brand purposes.

“We need to be clear on what we mean when we say purpose,” she said. “It’s about a guiding principle, which guides the organisation. It’s not a substitute for innovation. It doesn’t mean you can’t do lots of other things. But it must be at the heart of what you do.”

Bloomfield suggested that marketers should think of defining a purpose as a two-stage process:

- Look for a way to prove the brand’s difference to its peers. Figures from Millward Brown’s BrandZ database suggest that brands which have a strong “meaning”, “difference” and “salience” achieve typical annual growth of 20%, compared with 8% with weak scores for those three traits. “Building affinity with a brand through that purpose is important,” she added.

- If there isn’t a way to prove difference, look for a societal tension that the brand can credibly address.

Bloomfield cited Amazon, the online retail giant, as an example of a brand that was able to gain a purpose through option one. “Amazon absolutely has a purpose,” she added. “Much as people love to hate it, it’s improved the lives of people who use it. It’s super fast and reliable. That’s their purpose. It’s not a grand societal issue or a cause.”

As an example of what not to do, Bloomfield also pointed out a recent high-profile (and multi-award-winning) example of a purpose campaign that was not effectively linked to a brand. ‘Fearless Girl’ – a statue placed defiantly opposite the famous bronzed Bull in New York City’s financial district – achieved worldwide media coverage when it was installed. But nobody in the room at the WARC event correctly identified the campaign as a marketing initiative from investment firm State Street.

Which brand was this for, again?

Which brand was this for, again?

“Even now that it’s won every PR grand prix there is, nobody knows what it was for,” Bloomfield said. “A brand purpose has to fit with the brand. And there has to be a very strong reason behind doing the campaign.”

Tip 2: Aim for impact and memorability

Also talking at the WARC event, Heather Andrew, CEO of Neuro-Insight, the neuromarketing specialist, pointed out one common danger for generic, feel-good brand purpose campaigns: they tend not to be that memorable.

One project Neuro-Insight undertook for a household name brand with a new purpose ad, showed that the spot stimulated generally positive emotions, but fell short on one crucial metric: memory encoding. “They think – I like the message, but it’s not for me. We see this with many purpose-led ads. It’s not enough to declare a purpose, it has to have an impact too.”

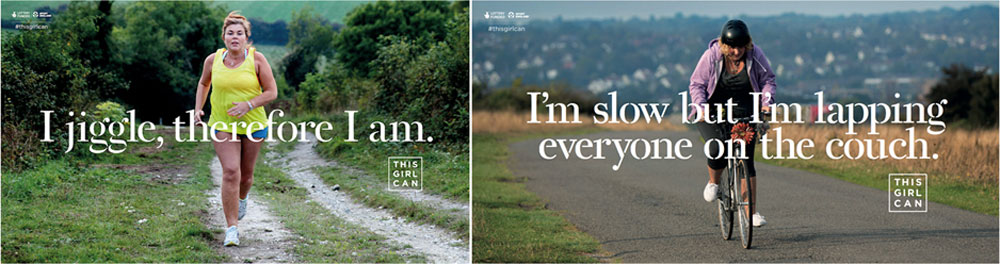

On the other hand, FCB Inferno’s work for Sport England in its ‘This Girl Can’ campaign was shown by the Neuro-Insight research to have “incredibly high” scores for emotional response – and memorability.

Viewers of one of the campaign’s videos showed the strongest implicit – ie, subconscious – scores immediately after the spot ended: in other words, when the memory was being encoded.

The memorable ‘This Girl Can campaign

The memorable ‘This Girl Can campaign

“Creativity is going to remain at the heart of advertising,” Andrew argued. “But the message needs to be personal, motivating and real. If you don’t put the brand – the call into action – into memory, it’ll just be entertainment.”

Tip 3: Be cynical!

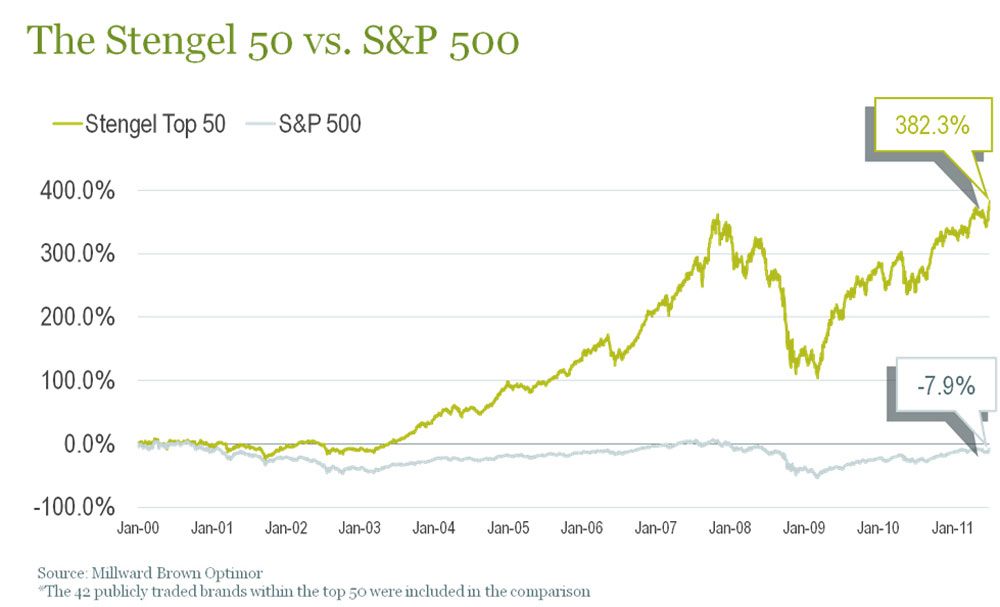

Some of the central tenets of brand purpose are also coming under attack. One of the most prominent recent pieces of purpose-related research, from Millward Brown and ex-P&G CMO Jim Stengel, compared the performance of 50 purposeful brands with the S&P 500, a US stock index.

Results suggested that, the value of the “Stengel 50” grew 382% between 2000 and 2011, while the main index dropped 8%. This in turn suggested that brand purpose leads to payback.

But Richard Shotton, Deputy Head of Evidence at Manning Gottlieb OMD, suggested that Stengel’s work is more “truthiness” than truth. “In marketing we need to spend less time taking people at their word, and more time looking at the facts,” he said.

A ‘truthy’ chart

A ‘truthy’ chart

According to Shotton:

- The brands in the Stengel 50 are actually 42 publicly listed companies, of which 16 are brands within a larger holding company. The performance of the holding company is what was measured: not an accurate indicator for a brand that only contributes to a tiny fraction of a holding company’s value.

- Of the 26 companies that actually have a stock market price, only 9 have outperformed the stock market since 2011.

- Many Stengel 50 brands don’t show a recognisable brand purpose. Many purported purposes are highly generic. For example, BlackBerry’s “ideal” is that it “exists to connect people with one another”. And a survey conducted by Shotton suggested that people are more likely to pin that brand ideal on (now-defunct) handset maker Nokia than BlackBerry.

“The problem is that he has made his definition of ideal so broad that it fits everything,” Shotton said.

And maybe adland in general is suffering from the same problem. Expensive spots suffused with feelgood purposes, without connection to the brand. A cynical public tuning out. And the vicious cycle being reinforced by the industry’s over-willingness to give brand purpose campaigns awards. Even a Creative Effectiveness Lion.