Kanban is one of the most talked-about, but least-understood, ways we have of managing digital product development. At least, that’s the impression I got from a recent talk given by David Lowe, a Kanban expert and Scrum coach, at General Assembly in London.

A quick Google search suggests that Kanban has something to do with improving production processes in Japanese car factories. But a look around the blogosphere shows it’s since been sucked into the Agile/Scrum/Lean vortex that powers so much product discussion these days.

This Kanban Method is a set of ideas for knowledge work. It’s based on Lean principles, and compliments the Agile Manifesto: it’s all about limiting “waste”, delivering work continuously, and making iterative improvements. And, I now believe, it’s a method that product managers need to know about.

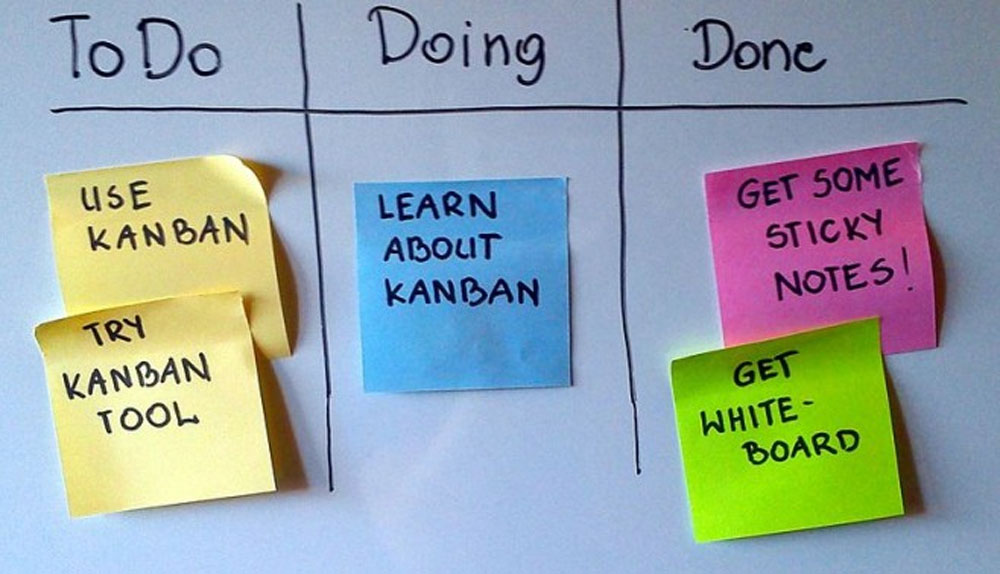

In common with other applications of Agile like Scrum, Kanban (I’m going to use Kanban and the Kanban Method synonymously from now on) works around a progress board: the sort of thing you can see on Trello, on JIRA, or on that part of your office whiteboard that’s organised in columns and bedecked with post-its.

The simplest Kanban board possible!

The simplest Kanban board possible!

But it differs from these Agile frameworks in other, crucial, ways. For one thing, Kanban is not a ‘big bang’ change. It respects the current processes of each business and emphasises evolutionary progress over revolutionary disruption. And, perhaps most importantly, it is a “pull system”: it aims to manage the amount of work in progress at any time in order to achieve an “optimal flow” of production.

Kanban in practice

A classic Kanban system is used in the Imperial Palace gardens in Tokyo.

Each visitor to the East Gardens is given a token as they enter; the visitor then gives the token back as they leave; after that, the attendant hands the token over to a new visitor, and the cycle continues. The number of tokens available is also the optimal number of people who should be exploring the gardens at any one time.

“The people running the garden know how many people can be there and have a great experience, not too crowded and not too empty,” Lowe said. “They’ve optimised the flow.”

These same principles, Lowe argued, are appropriate for software development. Here’s one way a PM can put it into practice:

- Prior to starting the project, the team agrees on the capacity of the system

- They use cards on the board (Trello, JIRA, whiteboard with post-its, whatever) to denote capacity

- They attach a card to each piece of work

- When they run out of cards, they stop taking on new work

- They only take on new work when a token is available: just like the garden, it’s one in, one out!

Kanban principles state that all environments are different – so the bullet points above are a suggestion, not a prescription. Another way of organising things in a more Kanban-friendly way, again based around the board, would be:

- Limit the amount of work in progress per column on the board

- Limit it across the whole board

- Limit it across the whole organisation!

Definitely a list that’s in reverse order of achievability, there.

Anyway, “you maximize the delivery rate because there is a finite capacity to the system,” Lowe added. “Limiting work in progress helps because it encourages the flow of work, and finishing stuff, rather than starting stuff. And generally, you should focus on finishing things, rather than starting on things!”

This idea ties in with Agile, because it encourages continuous delivery of work. But it differs from Scrum: in that framework, as Lowe pointed out, the system can be “overloaded”, as there’s “nothing in it to stop people taking on work”.

Measuring and managing the flow

Let’s assume you’re starting a project with a commitment to recognising Kanban principles. If you’re doing this, you need to be checking your flow of work, continually.

To do this, Lowe suggested, you should be using alternatives to the Burndown chart commonly used in Scrum. “With Scrum, you can’t predict outputs, and often, you don’t know where you are,” he added.

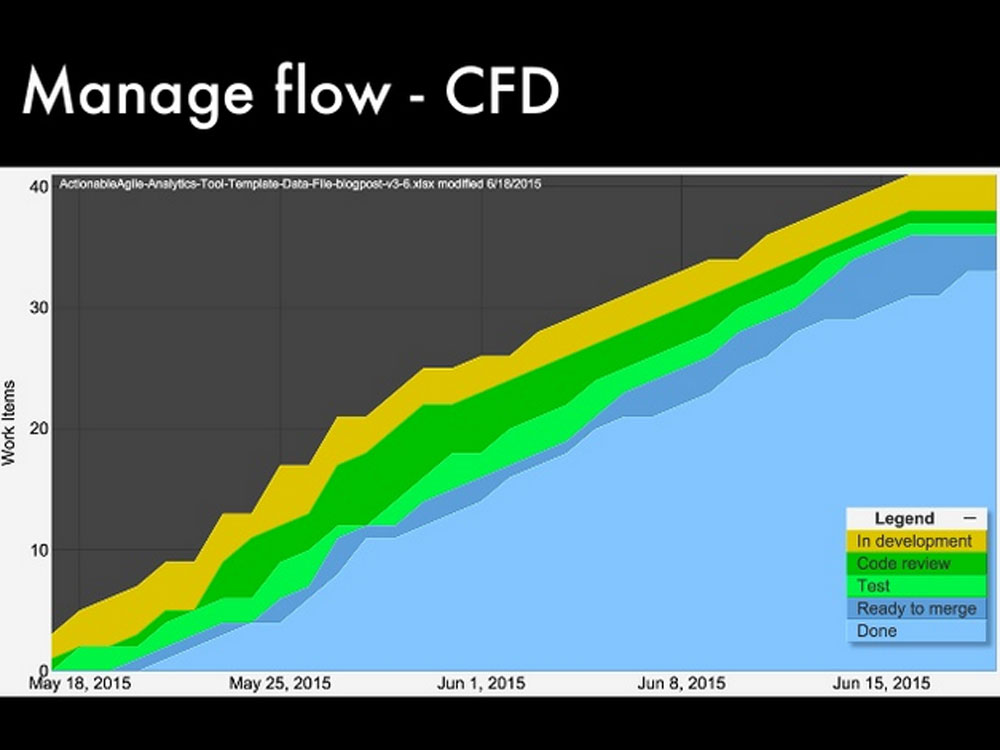

To get back some predictive control, there are a variety of Kanban-friendly reports you can use, all of which are based on the same data set: the number of items that are in each column of the board (In Development/Being Tested/Done). Unless you have paid-for tools like JIRA or ActionableAgile Analytics, though, you need to extract the data manually as you go along.

Chart 1: Cumulative flow diagram

Each day, count how many cards you have in development, being tested, and done. The X axis measures time, the Y axis the number of cards. As each task is completed, the chart builds up and to the right.

The crucial thing about this chart is that you want the bands to be as smooth as possible: the flow of cards/user stories/tasks in development and being tested remains stable. Your flow is optimised!

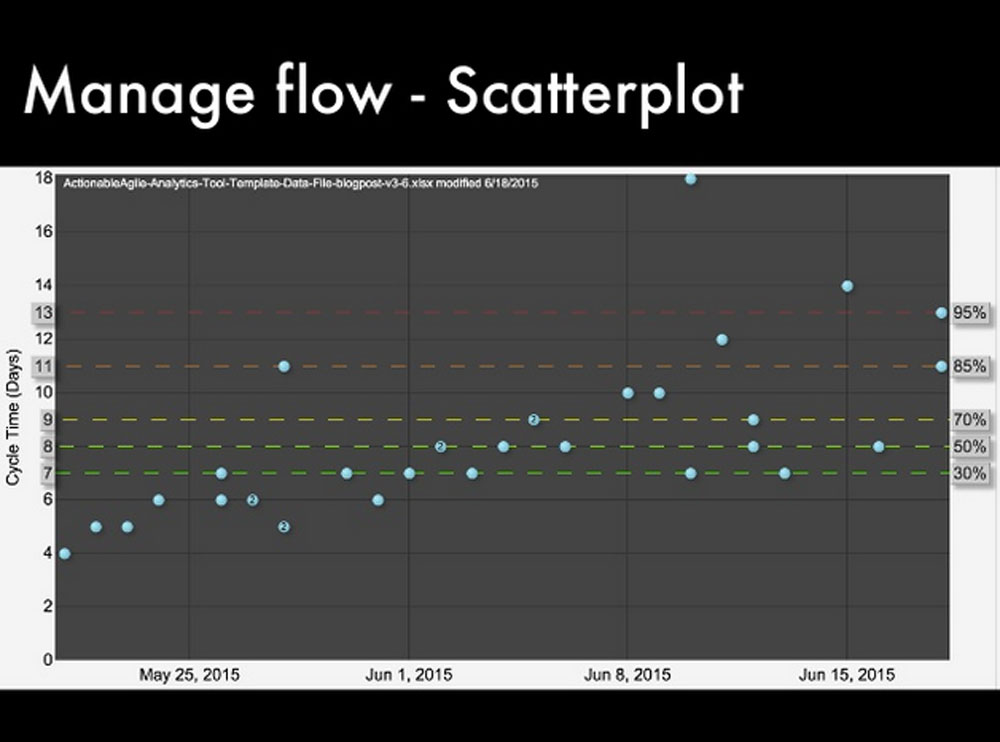

Chart 2: Scatterplot

This chart again measures time on the X axis, but differs from the chart above by measuring “cycle time” (how many days a card takes to complete) on the Y axis.

It is perhaps the most critical one for the PM, as it identifies outlier processes: those cards that take a lot longer than the others. You can use it to estimate how long processes will take in future.

Again, your aim is to limit the overall variation so that the flow is consistent. The more dots accumulating along the middle band of the chart, the better. Using this chart, Lowe added, means you can “investigate performance to attack sources of variability”.

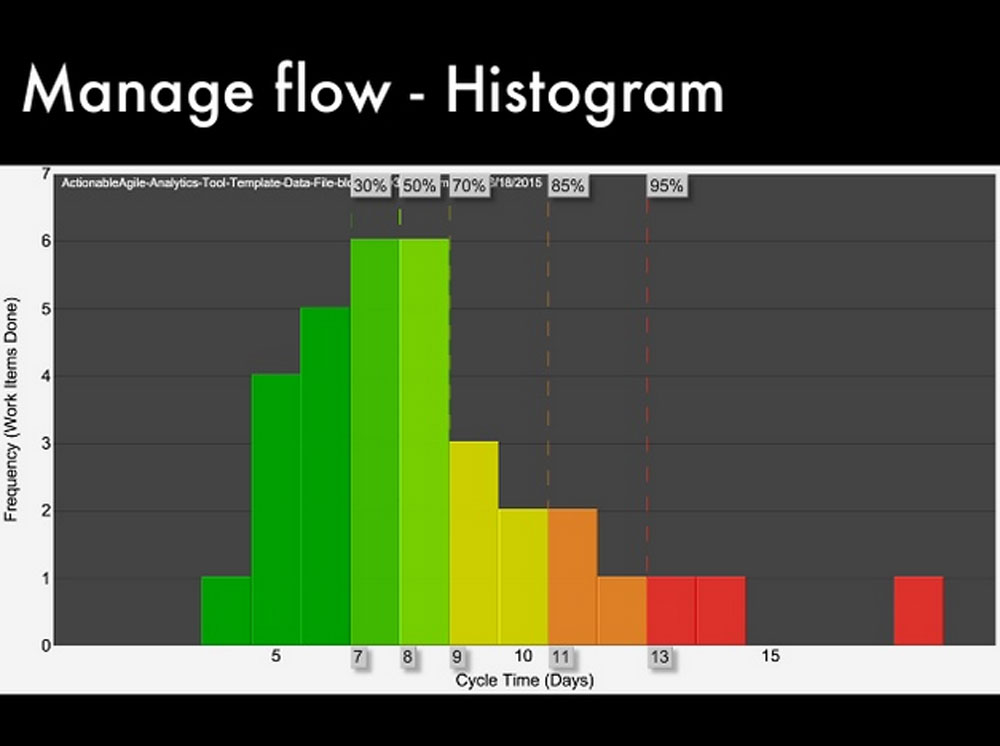

Chart 3: Histogram

The final chart is similar to the scatterchart in that it shows the distribution of how long each task in the project took. It differs in that it moves the cycle time to the X axis, and arranges the number of cards/tasks completed for each cycle time in bars.

“It gives us a much greater understanding than a Burndown chart,” Lowe added.

Kanban vs Scrum?

But all this should not be read as Scrum bashing. In fact, Lowe suggested, Kanban and Scrum can work together very well.

The way he sees it, Agile is a set of beliefs and so is Kanban. Scrum, on the other hand, is a framework for putting these beliefs into action. “There is nothing in Kanban that breaks the Agile Manifesto,” Lowe said. “Some say that doing a good Scrum system will be doing a lot of this already.”

While Lowe was careful to avoid directly criticising Scrum, for me the biggest thing to learn from the presentation was its implied critique of this much-hyped framework.

Scrum plays into the idea that working on lots of things at once may increase efficiency. By contrast, Kanban principles suggest that multi-tasking can actually be counter-productive.

The main thing I’ll remember is the idea that allowing too much work in progress is as bad as having too little – instead, you need to aim for optimal flow to get the best result.

And that, obviously, is a working principle that has far wider applications than just software development!

All images in this post are sourced from David Lowe’s presentation on Slideshare