We need a RACI!

So says somebody at some point in seemingly every big cross-functional project I’ve ever worked on. (Cross-functional here meaning that the team is made up of some combination of engineers, product people, and people working in other areas of the business.)

The cry goes up when progress is slow, deadlines are looming, communications aren’t getting through, and people don’t seem to be stepping up and taking responsibility for moving things forward. The cry also goes up whether or not a RACI was actually created at the project’s outset.

In my experience, RACIs tend to be ignored. Why? The business, generally, like the idea of a RACI. But the tech team disagree, seeing it as an old-school IT, waterfall-era relic. Sometimes out of this conflict some version of a RACI is created; when created, this resistance means the document isn’t always actively maintained; still less often, it is actually followed by everyone on the project team.

In my view, and at the risk of sounding like a prevaricating centrist dad, both sides have good points. Some form of limited RACI is actually useful in projects. But being ruled by your RACI isn’t very useful. Having a RACI but not maintaining or following it is actively un-useful.

Below, a defence of this view!

What is a RACI?

Simply put, it’s a table, listing the people or roles who make the decisions - or need to be told - about a thing. ‘Thing’ could be a process, an event, a project.

RACI is an acronym: standing for responsible, accountable, consulted and informed. Its origins seem a bit obscure, with inventors variously credited as the management writer Edmond F Sheehan (in the 1950s), to the consultancy Ernst & Young (in the 1970s). But wherever it’s from, the actual format of the matrix, as it’s meant to be used today, is clear:

- Responsible means “who is responsible for getting the thing done?”

- Accountable means “who oversees the task and makes final decisions about getting the thing done?”

- Consulted means “who provides information and support for geting the thing done?”

- Informed means “who is kept up to date with progress on getting the thing done”

Generally, who’s who on the RACI is documented, sometimes in a spreadsheet, sometimes in a page on the team Wiki, sometimes (god forbid) in a one-off email. Once created, it ought to be updated and referred to by people working on a project, throughout the lifecycle of that project.

Where a RACI fits in a project

One big knock many people have on the RACI is it’s a tool used by traditional project management, aka people who just don’t understand how things work, with a body of knowledge that’s belonged in the bin since we started getting dial-up modems at home.

It’s definitely an old-school tool, as I found out when I recently studied for (and passed, hooray!) my PRINCE2. This is the ne plus ultra of traditional project management frameworks, in the UK at least. And RACIs are absolutely part of PRINCE2.

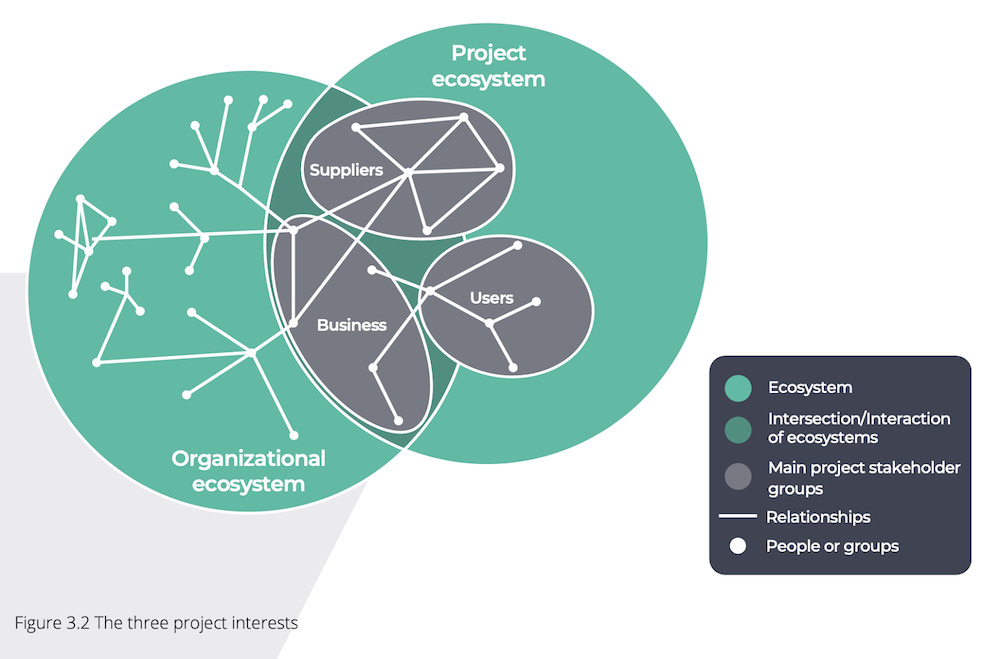

One thing that PRINCE2 makes - admirably! - clear is that projects are taken on in very complex environments. Every dot in that image above, taken direct from the PRINCE2 book, represents a person or a group, with different connections to each other. People work within the project, within the parts of the organisation untouched by the project - and sometimes both. The constellations of connections are too complicated for anyone to keep in their head: which leads to problems when you try to do something complicated… like actually deliver the project.

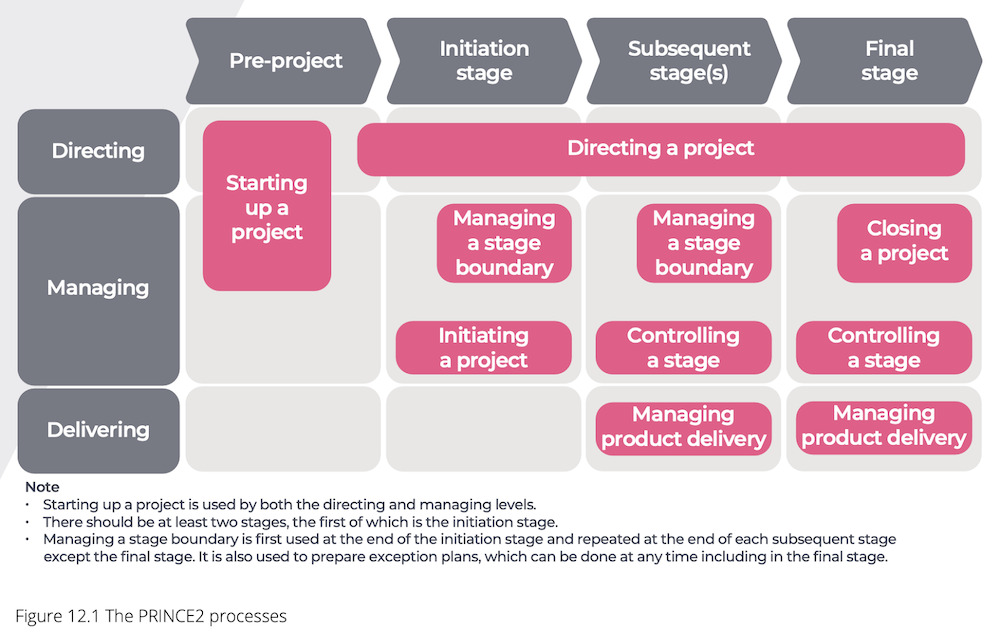

PRINCE2 tackles this complexity by teaching that projects should be managed in stages. These stages, from starting a project to closing a project, are the columns in the graphic below.

Meanwhile, people who are working on the project work at different levels of a hierarchy: directing (the executive and project board who authorise big decisions), managing (the project manager and their team), and delivering (the worker bees actually building the things required to get the project done). Those are the rows on the graphic below.

Finally, PRINCE2 projects are run according to seven processes, across different stages and with different people in the team. Each star in those constellations (in the first graphic) contributes to the project in some way, and their specific contributions are all within one of those pink bubbles (in the graphic above).

Which all contributes to a massive procedural problem - WHO DOES WHAT?

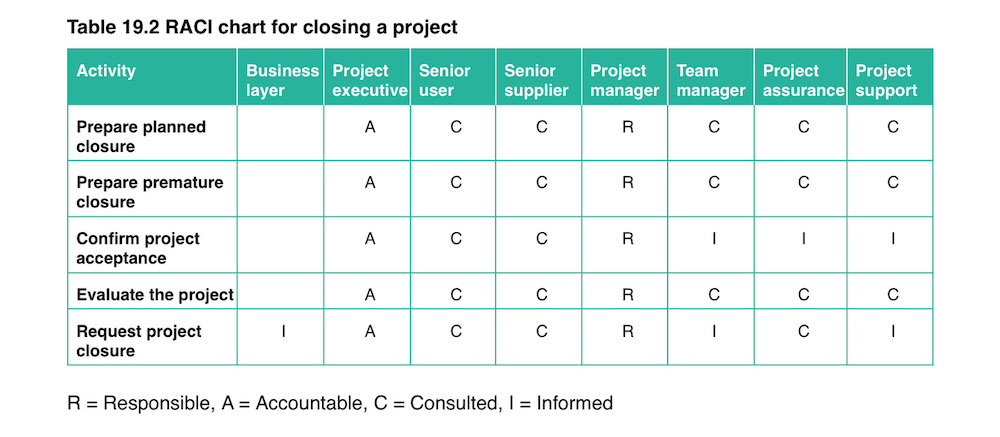

The RACI chart is an attempt to solve that problem. And, in PRINCE2, each of the seven processes come with their own RACI. Across the seven project roles. (Yes, PRINCE2 loves the number seven…) And each process has its own RACI, an example is below:

The activities listed on each row should be pretty self-explanatory “things you have to do to close the project”. You don’t need to worry about what all the job roles (the columns) do - though you can probably guess - the point is, they each have a R, an A, a C or an I. Generally, when closing a project, the executive is accountable, the project manager is responsible. Simple!

So, in theory, the RACI helps decomplexify complex environments, provides clarity of communications and lends certainty to project team decisions. In the real world, there are pros and cons to using this document.

RACI pros

The number one pro with setting people out in a RACI is the clarity it provides. It gives you a single place to look if you want to know who you should talk to when you have a knotty issue, and who will cut the knot and decide what to do.

There’s also a procedural advantage from the project manager’s point of view: the act of putting together a RACI can be really helpful to get a team aligned, focused and raring to go when beginning a project. It’s something that project people can work on collectively, in a workshop, thinking together about how things can work. It can give us hope for the future.

If maintained and applied (important caveat), it can help unblock teams and keep things moving, having a positive knock-on effect on the efficiency of delivery. With a living RACI, you’ll know who owns what, and where the buck stops. In larger programmes, the clarity this provides is invaluable.

RACI cons

If the caveat above doesn’t apply, though, and you don’t maintain and apply your RACI across the entire project team, you are in trouble.

Human nature means that taking on responsibility and accountability - sticking your neck out, taking the initiative - is hard for everyone. And it can mean that a person or a function who has been identified as responsible for something, simply refuses to take responsibility. Decisions are deferred, or kicked around, blockers intensify, the pace of delivery suffers. We all feel sad.

And, if the project manager lacks the authority to enforce the RACI, the document becomes all the more ignorable. Especially if the person identified as responsible or accountable feels themselves to be high enough on the food chain to ignore such attempts at enforcement safely. It’s just a table on a wiki, after all.

Tech teams, on the other hand, seeing the RACI as an old-school tool, can simply kill it at birth. I’ve worked with many developers who half-remember the bit of the Agile Manifesto that states working software is more valuable than “comprehensive documentation”, and assume that all documentation is to be resisted. This means that the project manager will often struggle to get a team of makers to engage in RACI creation, because it’s seen from the start as a heavy-old fashioned document, or a gateway to those huge PRINCE2 projects with different levels of authority, all the processes, all the reports, all the hierarchy.

How a RACI can work

So, a RACI has been created for good reasons, is potentially useful, but faces big obstacles to getting off the ground, and being maintained and followed by cross-functional teams.

How can a RACI work? Based on experience, here are five tips, again from the point of view of the project manager:

- Make the document as lightweight as possible. Rather than going full PRINCE2 and having a separate document for all the different processes associated with the project or initiative you’re doing, what about one RACI to rule them all? (The creators of PRINCE2 are totally fine with you doing that by the way, they call it “tailoring”. So long as you follow general PRINCE2 principles, you’re not going against the framework.)

- Get as much buyin as possible before you create a RACI. The easy way out, when faced with a sceptical team and responsibility-shy business, is going to be to put together a RACI by yourself, then tell the team we have one, then watch it quietly die! Instead, try to co-create it as much as possible with the teams themselves. If everyone can be in the room at point of creation, so much the better.

- If your work is solely with a development team working in some Agile framework or other, consider a team-level RACI scoped to what everyone does. In the Scrum framework, it’s easy: the Product Owner is responsible for the product backlog, the Development team is responsible for the sprint board. More generally, discussing roles and responsibilities collectively, especially at a project’s outset, is an activity that has benefits for everyone.

- Be brave in enforcing the RACI! If you see someone shirking responsibility who has been marked as responsible, push on it, politely. Be persistent and always be ready to point to the value of having a RACI. Actively listen to your colleague’s concerns, and be prepared to open a conversation on re-assigning responsibility if you need.

- In making things lightweight, consider making the matrix simpler! At the end of the day, a RACI helps make responsibility and decision makers clearer and gets us unblocked. What about an RA matrix if those are the two most important bits? (Hint: they are.) What about an “A team” list of accountables-only, if you want to be super bare bones?

That list above is one for me as well as you, by the way. As should be obvious, I don’t think we got the RACIs right in the projects I’ve worked for so far. But I still think that, if done right, they can do a job.

They’re not the key to project success. But they’re not a pointless relic either.