There are many ways of defining advertising, but none of them really work on their own. That’s according to no less a source than planning legend Paul Feldwick.

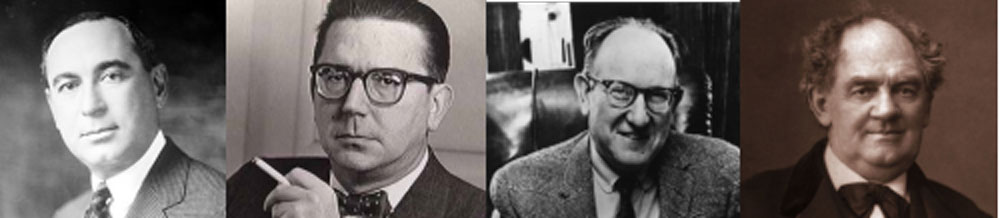

Advertising’s biggest theorisers over history

Advertising’s biggest theorisers over history

Here’s why you should believe him. Feldwick – in his role at BMB (later bought by DDB), was responsible for iconic campaigns including the 1990s Barclaycard ads starring Rowan Atkinson. More recently, he’s become something of an industry guru, revered by many (sample ad blogpost title: “Is Paul Feldwick God?”). So I counted myself lucky to hear him at ‘Unlearning’, an event organised by the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising, an agency trade body, and held in London earlier this month.

Listening to Feldwick speak, I couldn’t help but feel a bit guilty that, having worked in the industry for more than five years, and for a company that’s supposedly the world’s best source of advertising guidance, I didn’t know more about the history of advertising.

Luckily, Feldwick gave a useful primer. (And by writing this up, hopefully you can too.) He offered various historically-based theories of advertising in the presentation. These are among the six definitions discussed in his new book ‘The Anatomy of Humbug’ and in this article for Admap. Here are three that stuck out for me.

Advertising as salesmanship

This first theory started gaining wide currency with an incident that happened in 1903 – involving Albert Lasker.

Lasker was an executive at the Lord & Thomas advertising agency in Chicago, the largest agency of its time. And, one day, he was confronted in his office by a jobbing copywriter, John E. Kennedy, who pitched his own three-word definition of advertising: salesmanship in print. “You must give the a ‘Reason Why’,” Kennedy added. This way of putting things so impressed Lasker that, in the years following, Lord & Thomas used ‘Reason Why’ in its own branding when touting for clients.

Claude Hopkins spread the message further in his 1923 book ‘Scientific Advertising’. “The only purpose of advertising is to make sales,” he argued. “Treat it as a salesman. Force it to justify itself.”

For the book, Hopkins conducted research on mail order advertising: those print ads with a coupon attached for the reader to fill in and get an offer or discount. Due to the fact they were direct response ads, copy could be tweaked and optimised based on how many responses each iteration generated. Learnings from which were used by Hopkins to create some general ad rules: don’t be funny, don’t try to be clever, write an attention-grabbing headline that addresses your target audience; then, once you’ve got attention, load your body text with as much product information as possible.

Good advice – up to a point. “Those are still pretty good rules for direct response,” Feldwick told the audience. “Look at those ads for 14-day cruises down the Danube you still see in the Sunday newspapers. They still work!”

But what about other types of ads that might be doing something completely different? For one thing, Hopkins didn’t deal at all with ads that aimed to boost a brand, rather than fill in a coupon.

In stepped a clever market researcher: Daniel Starch, who invented the Starch Rating, a measure of attention.

To measure the effects of branding, he took research participants through a magazine, asking them if they had read each page: editorial and ads. “It’s incredibly simple data, but it had huge currency,” Feldwick said. “It was still around 15 years ago.”

Did the Starch Rating measure something important? “What Starch did was to take one element he could measure – attention – and sold it,” Feldwick said. “It’s a large leap to thinking that this one thing is actually important in itself, let alone that you should judge your agency’s work on it.”

After that, in the 1930s, there came George Gallup’s measure of “recall”, which was all about measuring whether people read the ad after they finished. Researchers didn’t take people through the magazine page by page, like Starch, but instead asked what they remembered about the magazine after they’d finished.

Gallup invented a concept that’s been hugely important in advertising, and the concept was taken a stage further by Rosser Reeves, head of the Ted Bates agency.

He’s best known as the inventor of the Unique Selling Proposition (USP) , perhaps the ultimate expression of the advertising-as-salesmanship theory, and for being notorious for writing repetitive, simple ads.

Reeves defined advertising in less than inspirational terms. It is, he suggested, “the art of getting a USP into the heads of the most people at the lowest possible cost”. Feldwick added: “He took the idea of a sales message from Hopkins, and recall from Gallup, and boiled it down into something that’s appropriate for the TV era.”

Across Lasker, Starch, Gallup and Reeves, “these ideas all come from the same root. It’s the Salesmanship Family Tree of advertising”. And many of these theories and terms are still commonly used.

Advertising as seduction

But, all this time, there has been a major, and very influential, alternative theory.

“Advertising as salesmanship [is] the dominant school of thought. But it is not based on any evidence, a particularly coherent theory, or is a generalisable truth,” Feldwick said. “We can all point to examples of successful ads that follow none or only some of these [salesmanship] points.”

The alternative theory – summarised by Feldwick as “advertising as seduction” – holds that advertising often works effectively without any conscious recall at all. In other words, the magazine tests are not useful, as the reader does not need to remember the ads in order for them to have been effective.

Advertising as seduction dates all the way from 1903, to an academic work by Walter Dill Scott. The author, a psychology professor, talks about creating “suggestion” – subconscious ideas – through advertising.

This was developed in the 1950s through the Motivation Research of Dr Ernest Dichter. “He was part of a group of Vienna emigrés to the US with some connection with Freud, who used that connection to sell their wares to advertisers,” Feldwick explained. So Dichter’s wacky-sounding ideas of brand ‘auras’ became a bit more credible by association.

While Dichter was “squashed” by Rosser Reeves and the TV driven Mad Men era, he might be getting the last laugh these days, thanks to neuroscience and behavioural economics-driven research, popularised by academics like Daniel Kahneman, that has uncovered shoppers’ subconscious motivations like never before. “We’ve seen a huge renaissance in this way of thinking, as we have a great deal more psychological research into System 1 and System 2 thinking,” Feldwick said.

Advertising as showmanship

And, beyond that, is yet another theory, one that looks out beyond narrow academic confines into the world of showbiz.

Feldwick put forward an unlikely advertising theorist who might have the strongest claim to defining the industry: P.T Barnum. This 19th century freakshow showman’s name lives on as a byword for baseless claims and sensationalism. But, as Feldwick pointed out, it’s Barnum who remains an undisputed master at both salesmanship and seduction.

His hoaxes remain legendary. From claiming that the four-year-old dwarf child Tom Thumb – the “smallest person that ever walked alone” – was actually 11, to gluing together a dead monkey and a fish and touting it as the “Feejee mermaid”, Barnum’s travelling shows were spectacularly successful for decades. Talk about going viral!

And, for Feldwick, his life illustrates an eternal truth of advertising. “The important thing was not that people believed it, it’s that people argued about it,” he said. “The ad industry gets very embarrassed about Barnum as its great originator. They want to be respectable and scientific. But, for me, his example has a lot to tell us as practitioners. We shouldn’t disregard it.”

Barnum’s influence can be seen in some of the most-awarded campaigns of recent years. For example, Volvo’s Live Test Series, which took the Creative Effectiveness Grand Prix at the Cannes Lions this year, features a stunt ad straight out of the Barnum playbook. Jean-Claude Van Damme’s “epic split” between two Volvo trucks, looked at this way, seems a fitting successor to Tom Thumb and the Feejee mermaid.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M7FIvfx5J10]

“The thing I think of most of all from this ad is the circus strongman doing his trick,” Feldwick added. “It’s pure humbug. Pure Barnum.”

And, when I interviewed him in Cannes after his win, Tobias Nordstrom at Forsman & Bodenfors, the creative agency behind the campaign, explained the success of the ‘Epic Split’ in a way that seems, looking back on it, quite Barnum like.

“You could say that we started off with the thought to use YouTube as our main media,” he said. “Later on we learned that it’s actually two main media – PR and YouTube – collaborating with each other. You need to get views on YouTube for the papers to start writing about it. Then when the papers start writing about it, views increase.”

Showbiz gets people, and the papers, talking and sharing. Advertising as showmanship, in other words.

Advertising as… simple?

So what’s it to be, salesmanship, seduction or showmanship? But the argument is not resolved. And, maybe, it shouldn’t be. “It’s very easy to polarise things one way or another,” Feldwick added. “But it’s not clear cut. There’s quite a lot that’s potentially useful to us in all these schools of thought.”

That might look like he’s hedging his bets. But the fact is, what makes advertising work is still an unresolved question. (And we haven’t even got into alternative theories such as Professor Byron Sharp’s forget loyalty, it’s all about fame mantra, discussed in this blogpost.)

Then again, if it was all resolved, not many people in marketing would have a job. And would maybe need to find work in… another kind of circus.