What’s the value exchange between me and Google?

Not to sound pompous, but this is one of the governing questions of my online life. But I didn’t give it a second thought until I noticed a few disappearing yellow stars.

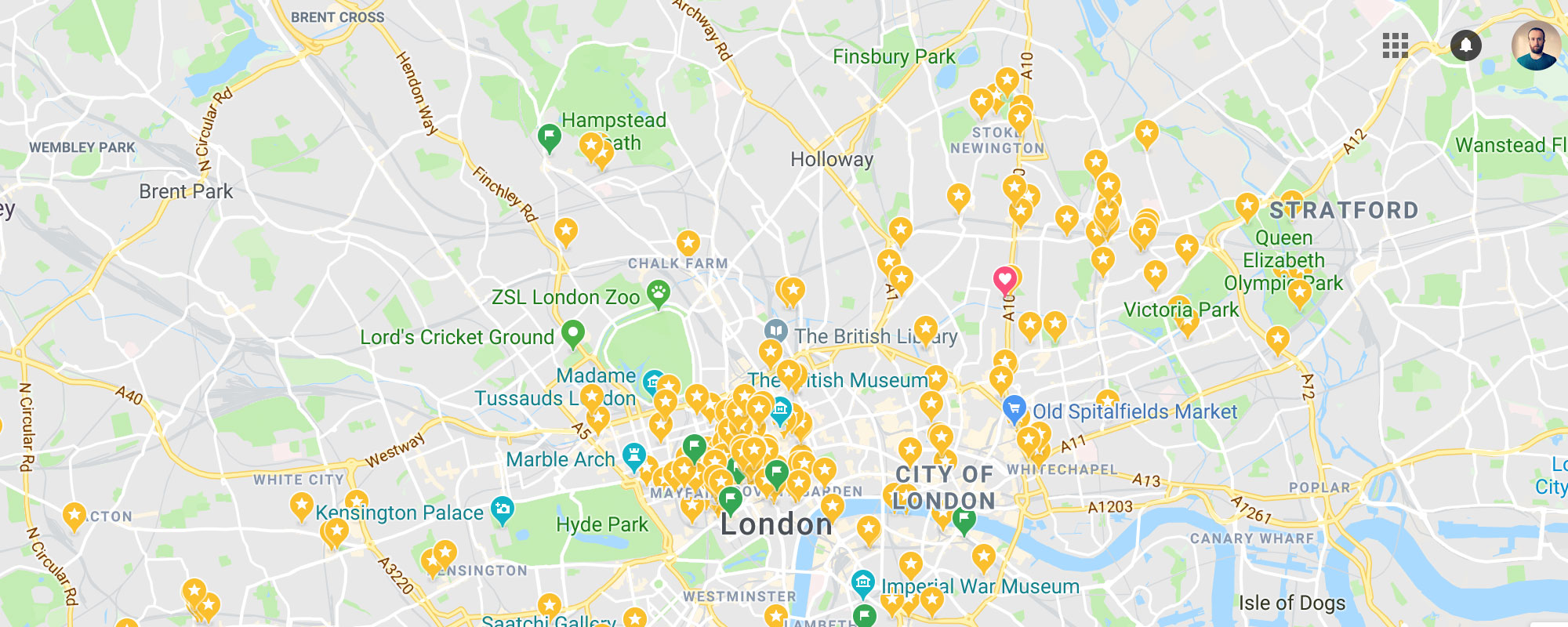

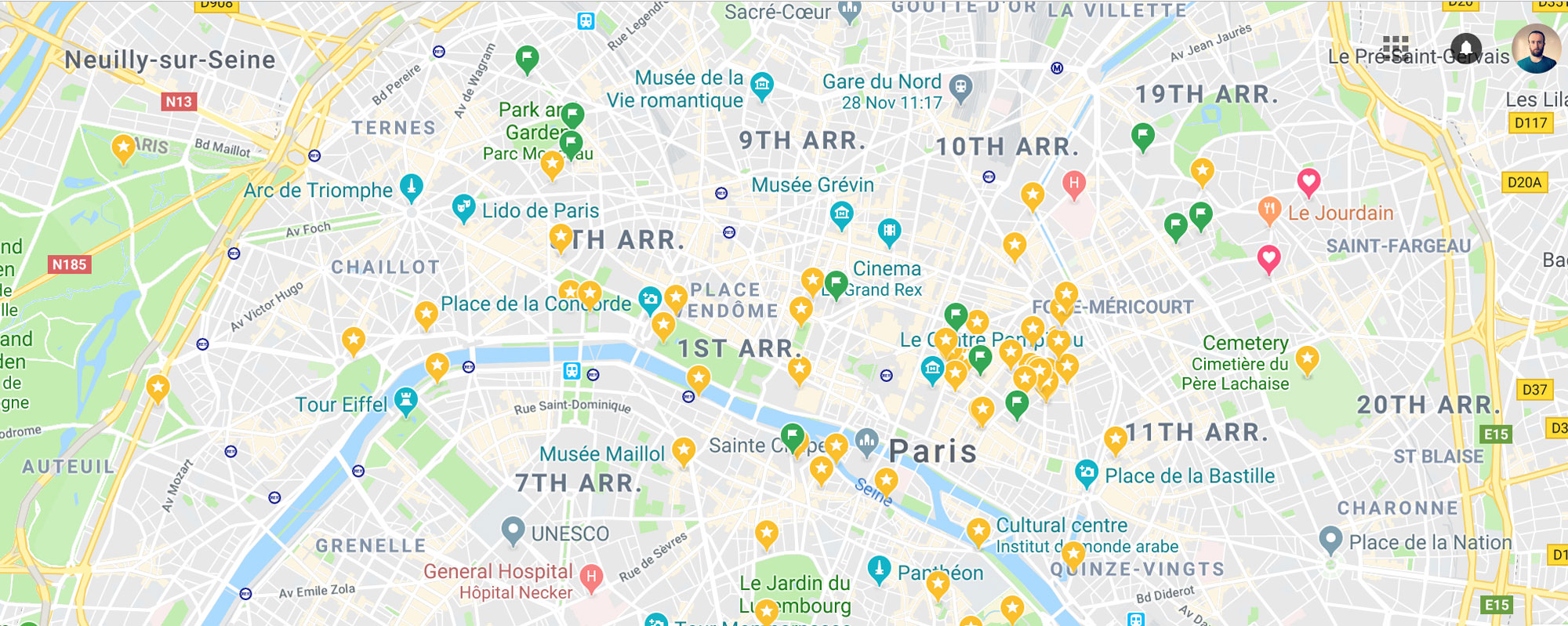

Do you know about the cult of the stars, flags and hearts? For initiates, it’s one of the most useful bits of one of Google’s most useful apps. Which is kind of like saying one of the most lofty crags on Everest or hottest spots on the sun, considering the Mountain View-based tech behemoth’s terrifyingly high standards of utility. Each spot on the map can be marked as follows: yellow star (favourite), green flag (want to go), red heart (extra favourite).

Users can add their own personal quirks – for me, I’m vanilla on the green flags, but use yellow stars to mark places I’ve been – regardless of recommendation – and red hearts to mark places I’ve lived or stayed. That yellow star quirk was my original mistake – more on that later.

Taking a step back: I get so much done with Google apps! At work, I measure and optimise online traffic through Analytics, Tag Manager and Optimise; I use Forms for quant research; sync all of my day-to-days through the Calendar. Elsewhere, Gmail is my main email provider, all of my personal documents are in Drive and I’m entirely dependent on Maps for getting around.

If I had the horrible choice of my Google account going down or my Apple ID getting hacked, I’d probably say goodbye to Apple, through my tears. Google apps have slowly colonised my online life over the years, ever since I got that sought-after Gmail invite in 2004. Or, since I noticed a far more quick, far more useful, search engine way back in the internet cafe days of the late 90s.

It’s not a secret what Google gets in exchange for its extreme utility: an enormous amount of personal data. Working in advertising, I realise that the possession of this data allows Google to sell a gigantic array of media spaces to advertisers. Which is seriously big money: Google’s revenues from advertising hit $28bn in the last quarter, out of $32bn in total.

Back to those yellow stars. After my initiation into the Google Maps tagging cult in mid-2017, I became a rabid evangelist. Especially useful for going on holiday – it’s changed the way I travel, too, for good and bad. These days, I’m in the business of switching those green flags – excitedly set pre-trip – into yellow stars, in a sort of bougie version of Pokemon Go. Gotta switch em all!

Google, being incredibly clever, and engorged on fatty slabs of user data, knows this too. Its (incredible) Trips app gives you a scrolling feed of sites, restaurants and museums to greenflag – yes it’s a verb – before you head off.

At this point, this story takes a nasty turn. One idle day, while onanistically thumbing over my map of New York on my phone (we all have hobbies) I noticed a sudden lack of yellow stars. Admittedly, I set them last summer, at the beginning of my map-marking habit, but I’m sure there were loads more of these, I told myself.

A couple of idle Google searches (obviously) and I uncovered the horrible truth: on mobile, the number of yellow stars that can appear on Google Maps is… capped. “There’s a rough limit of ~500 to show on the map at one time, depending on a number of factors,” a member of the Google Maps team wrote on Reddit with rage-inducing blitheness.

That’s why New York was looking so unstellar! These stars are deleted in chronological order, with the ones the user set first, going first. My slack standards for yellowstarring had bitten me painfully on my privileged arse.

Digging deeper, there is some wailing and gnashing of teeth – and arcane workarounds that are far too much effort for all but the biggest obsessives – on Google’s product forums.

I guess the cap is for technical reasons, as all yellow stars are present and correct on the web. But it knocks out a couple of use cases – for example, revisiting a city you haven’t been to for years, and not seeing that favourite restaurant you can’t remember the name of on your phone.

Which isn’t the most compelling use case when you think about it. How many of your favourite places to eat in your home city from, say, five years ago, are still as good – or are still going?

Capping the yellow stars doesn’t exactly detract from the utility of Google Maps, then. But it does provide a salutary lesson on the exact nature of the value exchange question with which I began this post.

You choose to give Google personal data, in exchange for useful services. But Google, unbound by a subscription fee and insulated by a dominant market share, doesn’t feel under any obligation to uphold its end of the bargain. It can take your stars away whenever it feels like it. And the user can whine to product forums and seek out workarounds, but they can’t bring the stars back – and they likely won’t go elsewhere.

After all, Google’s monopoly over online services is such that, in many cases, acceptable alternatives simply don’t exist. It’s like, what am I going to do – switch to Apple Maps?

So this user mourns some lost stars, stays in the cult, and adjusts their behaviour in the future.

Look at this nice empty place. It’s all ready for some greenflagging – and then some yellowstarring. If I do it, that’ll chop some more stars (late 2017 vintage) out of my mobile screen. I’ll survive, somehow.

And recall the truth of a much-used cliché: “If you’re not paying for the product, you are the product.”