Or, to put it another way, is advertising success achieved through incremental research, careful checking of data and sound planning – or is it more to do with the creative “eureka moment”? This “science vs art” question has troubled advertising’s biggest brains for decades. Remember that famous Bill Bernbach quote? “Advertising is fundamentally persuasion and persuasion happens to be not a science, but an art.”

The industry’s latest attempt at settling the matter came with a lively debate at the Edinburgh International Marketing Festival earlier this week. Arguing for the scientists were O&M’s global effectiveness director Tim Broadbent and Heineken’s Tom Gill; for the artists, Marketing Society CEO Hugh Burkitt and The Leith Agency’s Gerry Farrell. Perhaps unsurprisingly, in the final vote the motion – “This house believes advertising should be more about science and less about art” – was defeated fairly comfortably.

During the debate, both sides agreed that we need both science and art in order to be truly successful. But there was strong disagreement over which of the two should be given priority when creating an ad campaign. For Burkitt at least, it is art that, ultimately, gets the job done for marketers: “Scientists are good at the study of advertising, while artists are good at the creation of advertising,” he told the audience. “Science can take you only so far.”

To Farrell, the industry’s need to prove effectiveness – and many planners’ adoption of faddish marketing theories – was actively damaging. Effectiveness case studies, he added, could not forecast what would be useful in the future, as they only measure what has been successful in the past. Forget head of insight, for Farrell such marketing scientists would more honestly be called “head of hindsight”. Science’s Achilles heel is that there isn’t a secret formula for creating successful ads," he added. “Every single brief is different and works differently … The mystery of where ideas come from cannot be explained by science.” Instead, Farrell said that the genesis of many great campaigns based on an instantly-recognisable creative idea – from Sony Bravia’s Bouncy Balls to Skoda’s Cake Car – came about thanks to unplanned-for, unmeasurable serendipity. A creative eureka moment, in other words.

Comments from the audience – mainly made up of senior marketers – suggested widespread sympathy for this point of view. O&M’s Hugh Baillie suggested that the over-emphasis of “science” within the industry had come at the expense of art over recent years. “The quality of ads has declined because measurement has become more important in the boardroom,” he added.

Gill agreed that science was winning the debate within the industry, but reminded the audience that this victory could prove to be a good thing over the long term. He pointed to the vast sum being spent on advertising – around $470bn a year globally, on latest estimates. A sum which, Gill suggested, should not be entrusted solely to the artistic community. Moreover, the recent rapid expansion of the measurement tools available to marketers – social listening, neuroscientific advances and so on – is helping to create better ads. “Art is no longer core to creativity,” Gill said.

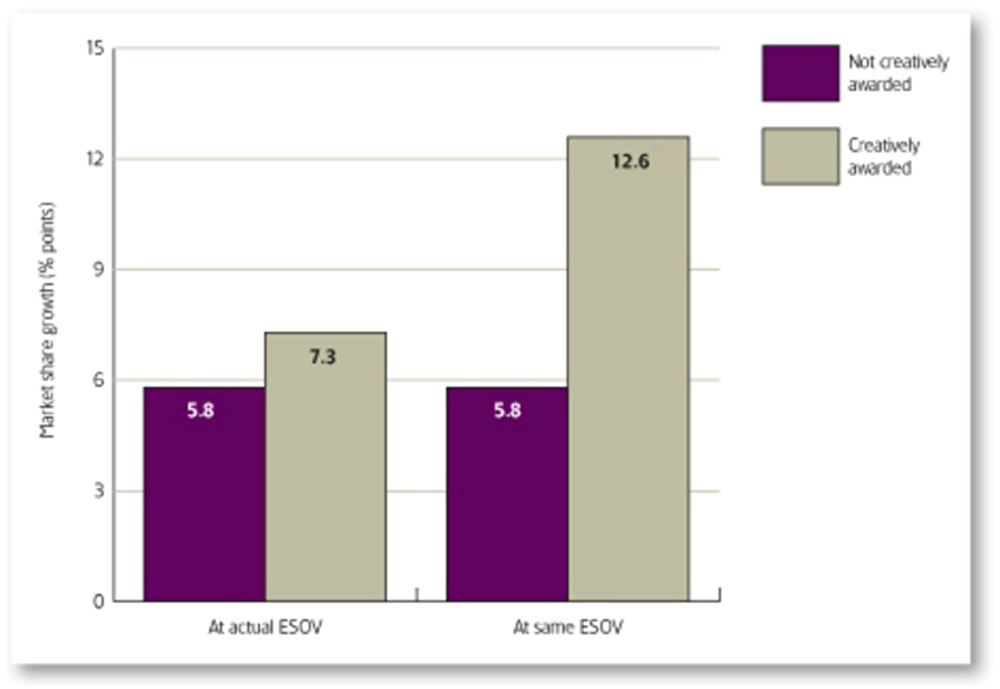

Broadbent’s argument for science over art was based on research from Peter Field and others, showing that “creatively-awarded” campaigns contribute significantly stronger business results than the norm. “Science has given creatives some very powerful ammo,” Broadbent argued. “Take that to the beancounters – creative campaigns sell more.”

More broadly, given all the talk of an impending global economic slowdown – and possibly a recession – marketers are going to have to get scientific to survive, he argued. When times are tough, the marketing budget is often the first thing that clients cut (Warc’s new Global Marketing Index report certainly backs this point up). And garnering data to support the assertion that marketing activity does indeed impact on the client’s bottom line becomes especially valuable in such circumstances. Moreover, in the agency world, such client cutbacks will lead them to hire fewer graduates – compromising creativity over the long term.

“That’s why it is our job to protect and defend the marketing budget,” Broadbent said.

Warc subscribers can read more about the presentations from EIMF 2012 in our full write-up of the conference. Other recent reports can be browsed in our Event Reports section.