Getting pricing right is a pretty fraught issue for brand owners. But what should the responsible marketer be doing to make things easier? The Psychology of Price, creative agency Draftfcb’s latest Breakfast Club event, held in London this morning, aimed to offer some answers. Behavioural economist Leigh Caldwell, author of a book of the same title as the briefing, and Draftfcb’s head of retail Niki Cook both offered their views – and both agreed that price-related decisions go a lot deeper than the actual costs of goods and services.

Of course, proper pricing is an essential concern for consumers. “The world is complicated, and you can’t objectively calculate the utility you get from any individual purchase,” Caldwell said. “But price gives us a shortcut through all that complication. Price is an artificial neatener - it makes decisions seem simpler than they actually are.” And to help make things simpler for brand owners, Caldwell offered seven different marketing tactics for them to add to their repertoires.

1) The Goldilocks effect

Shoppers like to compare prices of similar goods – and many, like Goldilocks in the fairy tale, like to pick the mid-priced option by default. Caldwell illustrated this point by using bottles of wine as an example: a margin-conscious retailer, finding their £6 bottles outselling their £8 bottles, can boost sales of the latter by introducing a £10 bottle.

“At first, the £8 wine looks like the posh version,” Caldwell said. “Add a wider range of prices and you shift up the average price. High and low ‘decoys’ push people to the middle.”

2) Anchoring effect

The order in which prices are compared can also be crucial to the final decision. An electronics store should therefore, according to Caldwell, put their higher-priced TVs closer to the entrance, so that by the time the customer reaches the lower-priced products they are more likely to see them as offering good value – a process known as the anchoring effect.

Yet this strategy can prove risky, with some customers, confronted immediately with the expensive models, leaving the store before getting to the cheaper alternatives.

3) Hyperbolic discounting

This tactic has its roots in neuroscience, with FMRI scans suggesting that the same part of the brain shows strong activity whether the subject is thinking about something painful as when they are actually feeling pain. This suggests that “high prices are the same experience as being punched in the face,” Caldwell claimed.

To get around this, some firms have introduced “pain-free” payment plans: for example, offering a payment plan for a £1,200 sofa consisting of 36 “manageable monthly payments” of £60. “They’re ignoring the pain, because they’re not experiencing it right away,” Caldwell said. Of course, that’s assuming that the customer doesn’t do the maths. These monthly payments, especially with the high interest rates charged by some companies, can lead to the user paying a lot more than they would have done by paying up front.

4) Price discrimination

With the growth of digital technology has come the possibility of dynamic pricing – offering better prices to some audience segments while charging others more. “If you look at your segments and target individual products as each of them, you generally get 50% more revenue than targeting everyone with the same price,” Caldwell added. “But there is a fairness argument here. People don’t want to feel that they’re being charged more for the same thing.”

5) Price as a quality signal

Simply increasing prices can also boost brand perceptions. Neuro-research has suggested that people get more enjoyment out of drinking a glass of wine they have been told is expensive than a “cheaper” wine. “You see this with marketing consultants – if they charge a lot, this suggests they’re really good,” Caldwell added. “Even though we know we shouldn’t, we take a high price as a signal for quality.”

6) Confusion as a strategy

Ever been driven to despair by inscrutable price lists? Whether it’s purchasing conference tickets or a low-cost airline flight, some methods for pricing seem designed to confuse. According to Caldwell, that’s exactly what’s going on. Some companies prefer a “deliberately complicated pricing structure”.

The major benefit and drawback associated with this strategy is obvious: in reducing like-for-like price competition by making objective comparisons very difficult, there’s always the risk that confusing pricing is just going to put people off from buying entirely.

7) Sales

The classic approach to boosting revenues through pricing is via discounts. It improves perceived value for money, with the drawback – from the brand owner’s point of view – of reducing the amount of revenues per unit solved.

To get around this, some companies have deliberately introduced products at a very high price for a short time, then introducing a heavily-marketed “discount price”. This tactic has attracted the ire of regulators, with UK courts recently fining Tesco, a supermarket chain, for a strawberry promotion for this reason.

Maintaining a price premium

With the pricing strategy determined, the next stage is to communicate this strategy to consumers. And, in her presentation, Cook agreed that such communications go way beyond advertising discounts. She was backed up in this view by research from Shoppercentric, a specialist insights firm, which suggests that only a quarter shoppers define value as being solely to do with low prices.

To Cook, there are four big value attributes that brands should follow in order to make their pricing strategy work – and to avoid having to employ “extrinsic rewards” such as larger pack sizes and discount offers.

1) Ease of shop

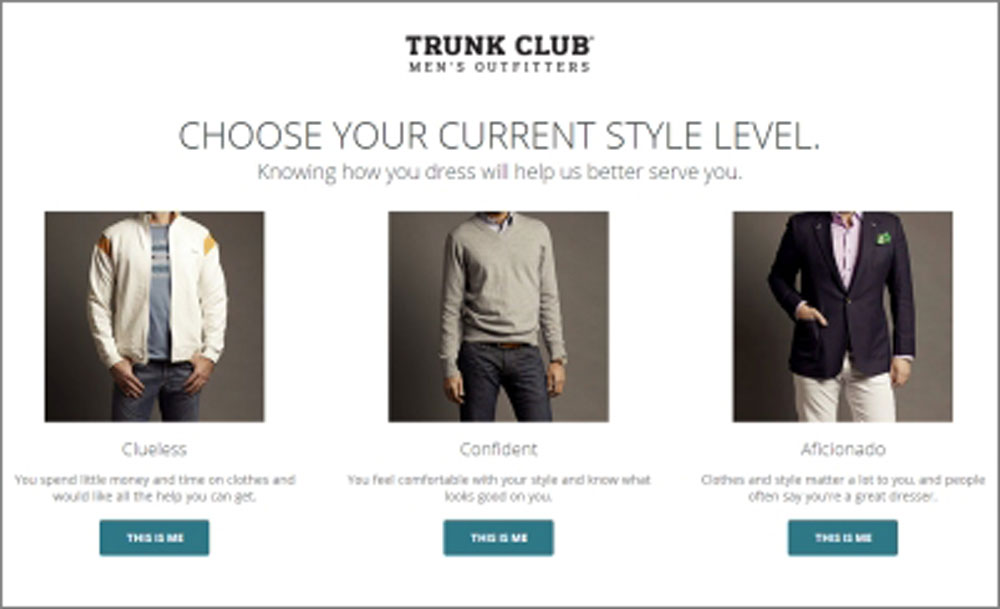

Brands should be flexible in order to justify their prices. For example, men-only online styling services Trunk Club asks potential customers to rank their “style level” before they start shopping.

After this, the Trunk Club stylist handpicks items suited to one of these three style segments, mails them out, and the user sends back what they don’t want. Shipping is free both ways. “Why go to the store when the store can come to you?” Cook added.

2) Empathy

The need for brands to establish an empathetic connection in order to justify prices has been established by initiatives like the One Pack = One Vaccine campaign from Pampers, a babycare brand.

Based on research showing that new mums have “enormous empathy” for other new mums, the P&G-owned brand launched a commitment in 2006 that every product sold would result in Pampers donating the cost of a tetanus vaccine to be used in the developing world: tetanus being a disease to which children are particularly vulnerable. Cook said this has led to over 300m vaccines being delivered so far.

3) Emotional reward

Getting in touch with emotions is another way of justifying a price premium. Cook cited the example of food firm Kraft’s iFood Assistant, an app that gets the brand involved in the planning stage, well ahead of purchases. The product offers a lot of recipes that users can navigate via voice commands, as well as a “what I have in my cupboard” search facility. The cumulative effect is simple, according to Cook: “It makes it easier for people to find and buy Kraft products.”

4) Experience

This last factor is particularly important for brick-and-mortar retailers faced with growing competition from online rivals. Cook said that retail brands should follow the massively successful example of Apple in building in-store experiences to attract passing customers – and keep them in the store long enough to try and buy.

One example of a great in-store experience is sportswear giant adidas’ adiVERSE interactive walls. “It’s an immersive and imaginative experience – that’s the important thing,” Cook added.