The whole Waterfall vs Agile comparison is a sham. It isn’t two competing ways of doing things. The Waterfall approach has never had serious support - not even from the inventor of the concept.

So many blogs, tweets and Medium posts about Agile have drawn the comparison over recent years. On one side, there’s the old bad Waterfall way of doing things - with bloated planning phases, long lead times, no user feedback, big releases, and no improvements to the initial delivery afterwards. On the other, the shiny new Agile way: learning from doing, delivering frequent iterative improvements, and having these improvements informed by listening to users.

This comparison is implicitly drawn in the Agile Manifesto and its associated principles, which posits the bad old way of doing things as over-emphasising “following a plan”, “comprehensive documentation” and ignoring “customer collaboration”.

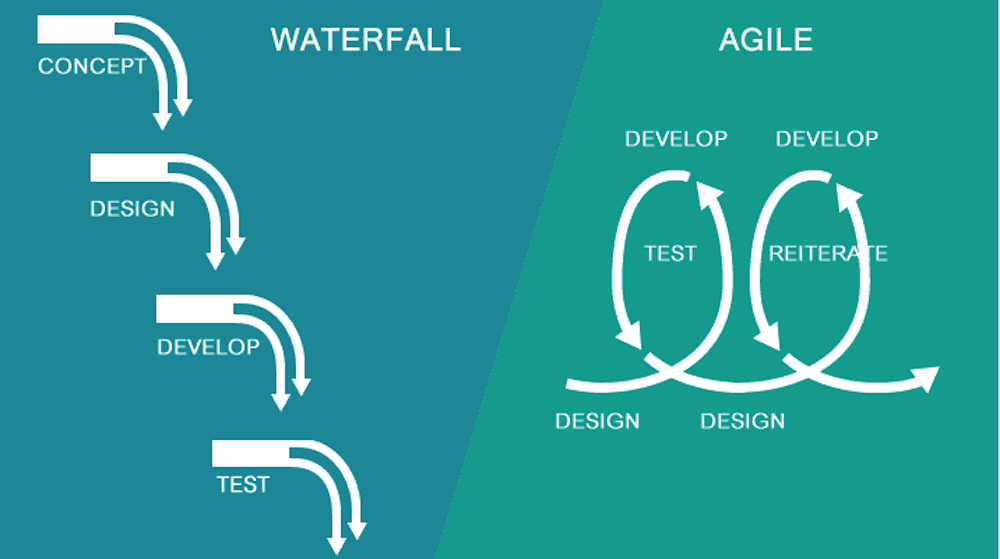

These days, the comparison is often illustrated in a graph. You’ve probably seen it before, drawing the contrast between the sad linearity of Waterfall, crashing down a staircase of stress, and the sinuous, virtuous Agile loops. Here’s an example.

Source: Planview

Source: Planview

But there are two problems with this very popular contrast.

First problem: far from being an upstart, Agile is nothing new. And it’s near universally (even if often superficially) advocated by the most traditional project management behemoths. When McKinsey is running its own “agile business units”, you know it’s game over. The Agile Manifesto was drawn up 20 years ago. And concepts in the Manifesto had been established business practices for decades before it was written up in the first place.

The second problem is more surprising. The contrast between Waterfall and Agile pre-supposes a conflict between two different ways of doing things. It follows that each ‘side’ has a set of advocates or fans. If that’s the case, though, where are the people who speak up for Waterfall? Has anybody, ever?

What if Waterfall was a strawman all along?

The penny dropped for me when I first read this great blog post from Dorian Taylor: not only does nobody speak up for Waterfall these days, he points out, it’s likely that nobody ever has, including the person who popularised the concept of Waterfall in the first place!

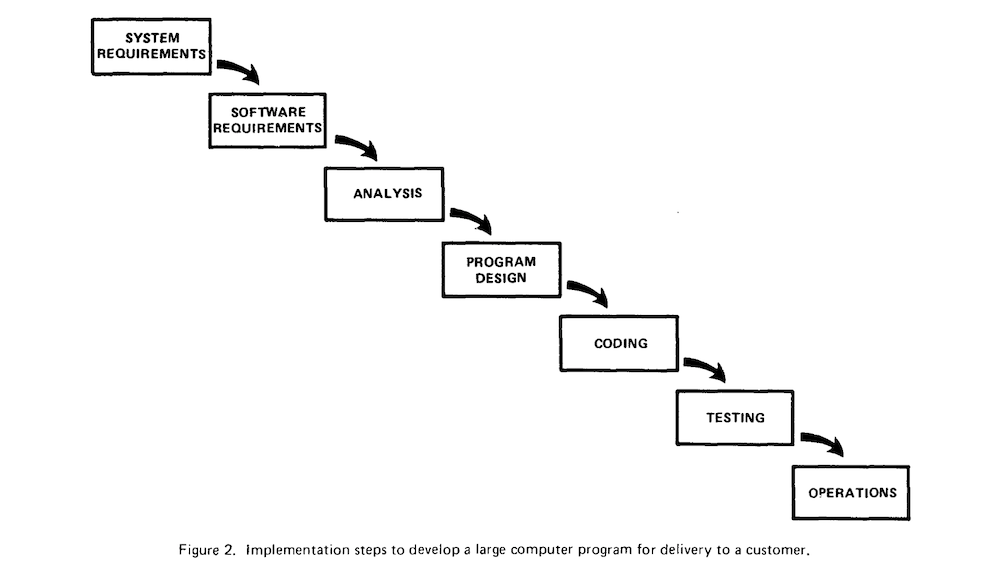

So, what was the source of the Waterfall? The classic graph - but not, interestingly, the term - was popularised in a 1970 paper by US computer scientist Winston W Royce, which is freely available online. I guess it was originally delivered at a conference, as it’s more of a polemic than a research paper.

(Sidebar: it’s unclear how, in the intervening decades, how ‘waterfall’ became the phrase to describe the process. The earliest citation is in a 1976 paper, which explicitly connects Royce and the word as if it was already in common parlance.)

Royce is up front about the opinionated nature of the paper in his introduction: “I have become prejudiced by my experiences, and I am going to relate some of these prejudices in this presentation,” he states. First up, here’s the original waterfall graph, from requirements-setting (top left) to delivery (bottom right).

You’d expect the inventor of Waterfall to hold this up as the right way of doing things, wouldn’t you? You’d be wrong. “The implementation described above is risky and invites failure,” Royce states, baldly. “The … method has never worked on large software development efforts and the costs to recover far exceeded those required”.

That’s right. The inventor of Waterfall invented it - as the wrong way of doing things. More than that, the 1976 paper that introduces the word Waterfall isn’t exactly glowing about the approach. Instead, it sniffily describes Waterfall a “top down” way of doing things.

So, nobody liked Waterfall from the start!

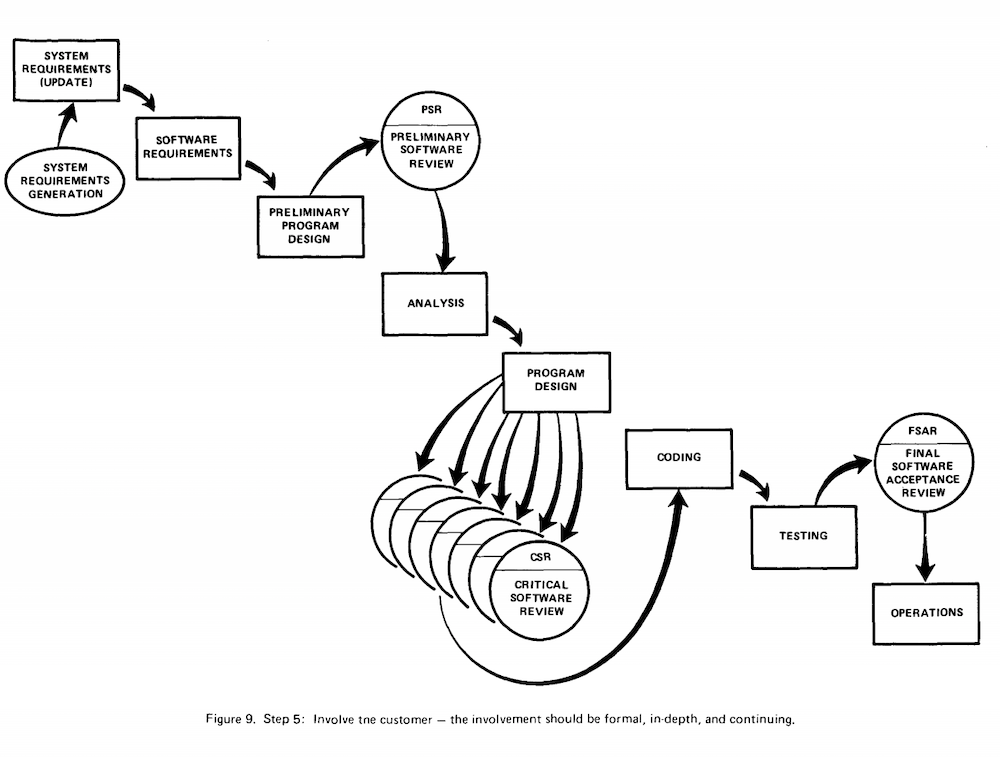

Royce’s paper isn’t a straightforward moan, though: he suggests a better approach. Incredibly, writing in 1970 - the era of humming room-size IBM computers, COBOL and FORTRAN - he advocates something that sounds very much like Agile. The better way involves iterative development, going to market early with a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) and incorporating user feedback in the final build.

Given that it’s 1970, Royce doesn’t use the word ‘MVP’ of course. His version, enabled by the technology of this time, is a “simulation”, a mock-up of the final thing:

If the computer program in question is being developed for the first time, arrange matters so that the version finally delivered to the customer for operational deployment is actually the second version insofar as critical design/operations areas are concerned… by means of a simulation.

Royce says we should aim to get this prototype to market roughly one quarter to one third the way through the project, in order to get “sufficient leverage” on what you finally deliver. And if you don’t?

Without this simulation the project manager is at the mercy of human judgment. With the simulation he can at least perform experimental tests of some key hypotheses and scope down what remains for human judgment, which in the area of computer program design (as in the estimation of takeoff gross weight, costs to complete, or the daily double) is invariably and seriously optimistic.

So, in other words, getting something out early to see what works allows the project team to validate assumptions, cut back on feature bloat and get a more realistic handle on delivery time - all impossible with Waterfall development. All important parts of Agile development.

Another ‘Agile’ benefit of prototyping early? We get user feedback, early:

What a software design is going to do is subject to wide interpretation even after previous agreement. It is important to involve the customer in a formal way so that he has committed himself at earlier points before final delivery. To give the contractor free rein between requirement definition and operation is inviting trouble… the insight, judgment, and commitment of the customer can bolster the development effort.

Towards the end of the paper, Royce gives us an alternative graph for his preferred way of doing things. Put crudely, it’s a waterfall graph with some Agile loops built in.

We’re not quite Agile yet, but that’s more due to the technology constraints affecting Royce and his peers, 50 years ago. Engineers and managers in 1970, working on physical hardware or software, were still tied to a single ‘OPERATIONS’ (or final delivery), meaning that development schedules were more linear. Hence the downwards slope, from top left to bottom right.

Royce is stuck in the Waterfall, dreaming of escape.

If nobody likes Waterfall, why are we still doing it?

Technological constraints trapped Royce and his contemporaries in the Waterfall. Why then - in a world of CI/CD, well-established delivery frameworks like Scrum, and the McKinseys of the world having their own Agile units - do so many of us in digital delivery still feel that way?

I’m firmly convinced that Waterfall as a concept retains such power, even as a strawman, because we see that way of working again and again in our working lives. We live the reality of business stakeholders bringing solutions to us rather than problems, working on fixed requirements ahead of development, being HIPPO’d (that’d be ‘highest paid person’s opinion’) rather than building according to user needs, and being tied to stressful and error prone huge releases.

Taylor is scathing on this point:

I want you to consider instead the possibility that Waterfall came to exist, and continues to exist, for the convenience of managers… who, more than anything else, need you to promise them something specific, and then deliver exactly what you promised them, when you promised you’d deliver it. There exists many a corner office whose occupant, if forced to choose, will take an absence of surprises over a substantive outcome.

And he doesn’t have much hope that Agile can save us from this reality, because it doesn’t cover “anything higher up the chain than project management”. Agile ceremonies and artefacts are, from this point of view, “all tactical stuff”, that doesn’t really change anything.

Failures to implement Agile principles are often easily diagnosed as side effects of the constraints of antiquated procurement and contracting practices.

It follows therefore that in order for projects to be Agile, they need to be delivered in an Agile organisation. For an organisation to be Agile, it follows that each unit follows these principles. That would include very un-Agile functions like procurement and drawing up contracts. And there are many great reasons why these units are not Agile. Who on earth wants to release an MVP legal contract which we all iterate on, after all? Though the retro on that would at least be very interesting…

I think that Taylor’s placing the blame for the pervasiveness of Waterfall thinking mainly on managers is fair enough, but also lets people lower down the chain off the hook. I find in my job as an agile delivery manager (let’s face it, another term for project manager) I constantly find myself coming up against my own ‘waterfall thinking’, whether it’s in pushing for more potentially unnecessary documentation, advocating larger but later releases, or, afraid of a looming deadline, supporting the cutting back on prototyping and user research. All of which is impelled by the need to get through the day-to-day hurly burly of working life, even if it stores up problems for the future.

While our managers cast us down the waterfall, sometimes we don’t need much persuasion to jump. Sometimes we jump ourselves. While Agile rationally makes sense as a better way of doing things, it’s much easier to talk about in the abstract rather than just do. While Waterfall, when you take a step back and think rationally, causes a whole lot of problems, but when you’re in the thick of things it makes instinctive sense - for us and our managers.

A few conclusions

So, now I know that:

- Agile is an attractive idea that’s reached maturity in the business world

- Nobody ever liked Waterfall, including the person who popularised the concept 50 years ago

- Despite these intervening years, Waterfall is still instantly recognisable to people working on digital projects

- There are obviously loads of factors behind this being the case! But one major one is - our managers

- And, if we’re honest, we in digital teams also reinforce Waterfall thinking ourselves.

That’s a tough set of truths to accept, as it means that being truly Agile, and working in a truly Agile environment will be a hard uphill battle for everyone. And that doing so will involve overriding some natural instincts, and persuading better-paid people to override theirs. Very often, it will be doomed to failure. Agile benefits may only be, as Taylor says, “tactical” - and maybe we should be happy with that.

A more achievable conclusion for me is - the next time I see one of those graphs with the bad old Waterfall staircase on the left, and the nice new Agile loops on the right - I’ll give it an eye roll. The easy dichotomy is not so easy. It’s not a comparison of competing ideologies. I’d argue it depicts a battle many of us are fighting, between our instincts and our rational brain!