It was a normal winter’s evening on London’s worst street. Just out of the office, I walked towards Oxford Circus, up from the Centre Point end, where the tourist tat shops selling Union Jack keyrings, hoodies and wheelie suitcases give way to the fast-fashion chain stores. I began to cross the road, around the point I’d crossed hundreds of times before, on hundreds of previous commutes home.

A sudden charge in the atmosphere: a bike and a car were approaching, and the car was accelerating quite a bit, right behind the bike. The cyclist was an easy urban type to spot: middle aged, black lycra, racing bike, pedal clips, a backpack with a fluorescent rain cover. Serious kit, maybe a lawyer on his way west from the Strand. The driver was clearly a type too: white BMW with a superfluous spoiler. Suburban kid in his twatmobile showing off in the city.

Things suddenly felt dangerous, on edge, not quite right. Mainly because of how fast they were going. Honking incessantly at the bike, the car was revving its engine. All seemed to fall silent around it. Things were getting weird. The cyclist, while pedalling hard, turned half way and gave the finger to the driver, yelling through his windscreen. Both faces contorted. He was almost rear-ending the bike, whose rider seemed to be pedalling for his life, directly ahead of the car. Or maybe he was also racing it, getting in the way, daring it to come closer.

As they approached the crossroads, the car continued to press the cyclist, accelerating into the bike’s rear wheel. They touched. Immediately, the car shrieked to a stop, the cyclist on the ground. Probably an overtaking manoeuvre gone wrong. Or maybe, in a split second of blind anger, he’d really meant to mow him down.

All of this happened so fast, no more than five seconds after first spotting the vehicles approach.

The cyclist somehow escaped the car’s wheels. And I heard the rush hour crowds again. screaming at the impact. Hundreds of people could have seen it happen. As more and more people gathered around it, the driver tried and failed to get away in the car. Smartphones, the essential contemporary tool for vigilante justice, were whipped out - mainly, it seems, to film the driver and his car number plate. He wasn’t going to get away with it.

People helped the cyclist up. The driver stayed outside his car, surrounded by the crowd. “He hit me! He fucking hit me!” he said, in justification. He meant the car’s bonnet.

That’s one of the more spectacular skirmishes in the endless, grinding cold war of daily commuters: bike to car to pedestrian, two wheels versus four versus none.

The conflict is getting worse. As the massive centrifugal forces of international finance and politics suck ever more people into the city - London’s population regained its all time high of 8.6m early last year, a total projected to increase to 10m by 2029, growing at a rate of nine people every hour - there are more and more people making the daily trip in and out. Brought together by necessity, but separated by mutual loathing, the daily friction between these residents is at its peak during these commuting times.

This conflict has been going on for centuries. London’s urban geography of cramped medieval streets isn’t going to change, even as the crowds increase. And things were bad enough when the city was smaller. Remember Dickens’ famous opening to ‘Bleak House’, viewing the enormous, filthy city in “implacable November weather”, notes the crush and squeeze of the city’s commuters:

Foot passengers, jostling one another’s umbrellas in a general infection of ill-temper, and losing their foot-hold at street-corners, where tens of thousands of other foot passengers have been slipping and sliding since the day broke (if the day ever broke), adding new deposits to the crust upon crust of mud.

And, of course, TS Eliot’s vision of the hordes of City workers flowing over London Bridge as an army of the undead leant a hellish tinge to proceedings:

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

Flowed up the hill and down King William Street.

Writing 20 years later, Patrick Hamilton, in ‘The Slaves of Solitude’, saw the acute dilemma of the city traveller in similarly inhuman terms.

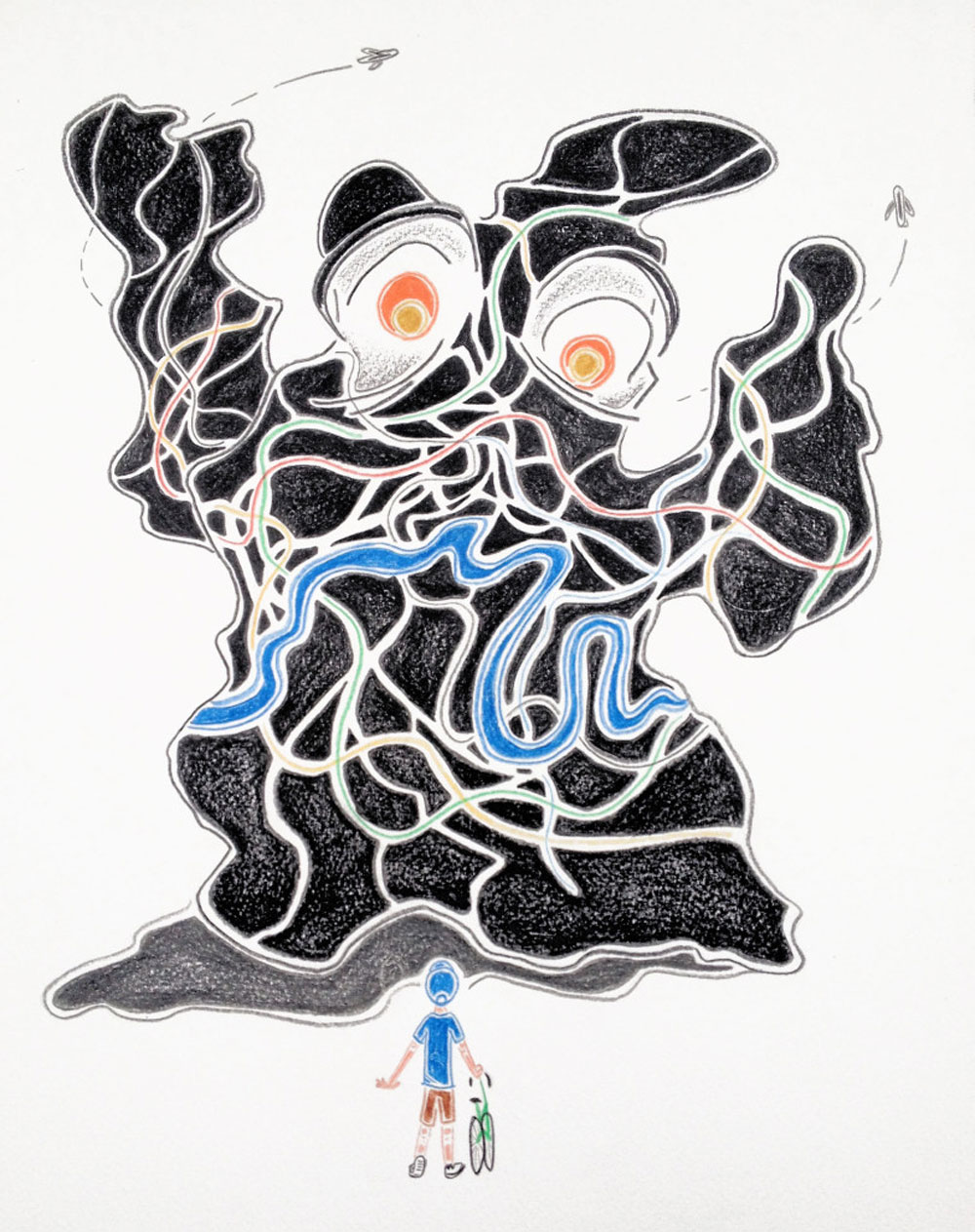

London, the crouching monster, like every other monster has to breathe, and breathe it does in its own obscure, malignant way. Its vital oxygen is composed of suburban working men and women of all kinds, who every morning are sucked up through an infinitely complicated respiratory apparatus… into the mighty congested lungs, held there for a number of hours, and then, in the evening, exhaled violently through the same channels.

The men and women imagine they are going into London and coming out again more or less of their own free will, but the crouching monster sees all and knows better.

Recent transportation trends only serve to up the stakes of the conflict. The big growth area in commuting is of a population that unites everyone not part of it in annoyance and repulsion: the city cyclist. A report from Transport for London suggests that cyclists could soon outnumber cars in the city centre rush hour. Take your pick of the reasons for this trend: most likely it’s due to the daily soul suck of travelling on London’s overcrowded, and enormously expensive, trains.

A recent exhibition at the city’s Building Centre predicted that the number of daily trips on the city’s roads will grow from 26m today to 32m by 2041. Of this total, 750,000 are taken by bike, though this is on track to double in the next decade.

These lycra-clad interlopers, in their attempt to escape the suffocation of public transport, have upped the pressure on the city’s infrastructure. Concern abounds, annoyance multiplies. Each cyclist death is covered diligently by the media, and protested with choreographed “die-ins”. Political arguments rage: with almost half of fatalities caused by freight vehicles should they be banned in rush hours? Uncertainties abound, apart from the deep conviction of moral superiority on each side.

If cyclists are fighting a war, their body count remains relatively low: 14 died on London’s roads in 2014, and 13 in 2015. But cycling feels dangerous. Trust me, I’ve been doing it for years. That evening on Oxford Street was quite unusual, as most of the time I’d be biking home. Just as my dad did for decades. No car. No idea how to drive, not much desire to learn, either of us.

Since February 2013, I’ve cycled 7,390km: that’s a trip from here to Brazil. I know this because I track it on a spreadsheet, conducting the nerdy ritual of recording the readings of my on-board ride tracker, each evening. (In my defence, I could get far nerdier: have you heard of Strava?)

I spend hundreds of pounds a year on my road bike. I ride with clips, and in lycra. My bike has gears. My backpack is cheap and brand-free, covered by a waterproof wrap. All of these details are important differentiators for my specific two-wheeled tribe, of which the city hosts several. It means I’m part of the city commuter tribe, separate from the hobbyists wobbling on hybrids one one side, and from the Carhartt wind cheater and knitted cap-clad try-hards on fixies on the other.

While the tribes are separate, they’re all on the same side in the war. They have two hated enemies: motorists and pedestrians. Hatred comes from fear. I fear the commuting mum with her precious (tiny) cargo marooned in the back of her submarine-size 4x4, prone to swerving to the pavement with no warning when she approaches the drop-off point of her (fee-paying) school run; I fear the pensioner hunched over the wheel of his ancient hatchback, shopping bags piled up on the back seat, oblivious of his mirrors or traffic lights; I fear the harried Uber driver, identifiable only by the dash-mounted satnav lighting up his car’s interior as he switches lanes to take an unanticipated turn at the last minute; I fear the truck driver because statistically he’s the most likely to kill me; I especially fear the Taxi driver, driving a cab too expensive for me to ever hail, arrogantly cutting up everyone else as he rushes to his next fare.

In case you haven’t guessed from the list above, these hatreds tangle unhealthily into the dark hinterland of my pre-existing, subconscious, class and gender prejudices. But, every now and again, something happens that suggests I’m right to hate, or at least fear these people. How about the teenage girl getting out of her car next to the Vue cinema on Shepherd’s Bush Green last spring, opening the rear door in front of me as I drifted by, sending me flying over the curb, bending my wheel and my axel and giving me an interestingly-coloured bruise but, thank god, nothing more. And the middle-aged man in the sensible Ford who rear-ended me when I slowed down for a red light on the exit to Hyde Park six months later: again, I stood up more or less unhurt. But what about the next one who hits me, what will happen to me then?

Of course, they hate me too. My adrenalised limbs and frightened mind loosens my inhibitions, and my behaviour gets worse. I’m in their way - of course I am. I slow them up. I enjoy slowing them up; I welcome their hatred. I’m looking for a reason to hate them more. If they swerve on me or overtake too close, they get a look through the windscreen. Maybe I’ll brush the mirror too if I catch them up at the next lights. If they beep me and I’m in front, I’m riding slower, just to annoy them. I really don’t want to stop entirely at zebra crossings, tired, with my legs full of lactic acid and close to home: so I skim past them as they walk across. And if you try to cross in front of me and it’s not on a marked crossing, I’m not about to stand for that moral outrage. I’m going to keep on going at you, maybe swerving a bit towards you to give you a scare. Stepping off the kerb while looking at your phone? I’m shouting at you. If you were in the car, or walking on the street, you’d hate me too.

In fact, I hate me too. Because on the rare occasion I’m riding shotgun in a private car, my first thought is: who are all these fucking cyclists everywhere, and why are they slowing me down? So add hypocrisy to my long list of sins.

Plus a lack of empathy. Safe in the passenger seat, I can’t even empathise with myself as I watch me pedal along in front. And, given that this lack of empathy is shared by pretty much all of my fellow commuters, what chance do we have of finding common understanding?

From experience, it’s easy to imagine what happened with the man in the white BMW. I’ve been there so many times before. On edge, pressing through the congested city centre, the driver must have pushed and prodded at a traffic light. Maybe nosing the BMW into the advanced stopping box supposedly reserved for cyclists to get some safe separation from the rest of the traffic, but in reality routinely ignored by the more aggressive private drivers, and universally ignored by taxis.

The cyclist, clad in his expensive kit, on his pricey bike, annoyed at the invasion, must have pushed in somehow. That universal sense of affront when the enemy gets the upper hand. That moral outrage. Maybe he clipped a wing mirror. Maybe he passed on the outside, too close for the driver’s liking. Words are exchanged. Both men adrenalised. No understanding between the boy racer in his white sports car and the middle aged lycra lawyer. The class difference driving them apart still further.

Then, the cyclist’s weapon - the most tempting thing to do when harsh words are exchanged, when you’re confronted with the twat in the twatmobile - the flat palm on the bonnet: bang, bang, bang! He hit me! The lights go green. The pair move off, across Tottenham Court Road, into the more down-at-heel end of Oxford street, past the trinket shops with their tourist tat.

The man in the white BMW’s days terrorising the clogged arteries around Oxford Circus are numbered: all of the city’s mayoral candidates for the 2016 election want to pedestrianise the area. But the rush hour monster will keep on breathing: in, out, in, out. And, as we shoot through its infinitely complicated respiratory system, we’ll continue bumping into each other in the rush.

The illustration in this post is by Eduardo Féteira.