The painter Giorgio Morandi lived at 36 via Fondazza, in a quiet corner of Bologna. Morandi, a painter of calming yet weirdly intense still lives, had a reputation for obscurity, separation, reclusiveness. But the address is world famous: so much so that it’s been converted into a museum, open to the public for a couple of hours a week.

Three rooms in the apartment are glassed off, preserved as they were when the artist lived. You can see Morandi’s sitting room, with yellowish wallpaper and an uncomfortable-looking sofa. There’s his dingy, cluttered corner studio. And next door is a small closet, with floor-to-ceiling shelves, loaded with rows upon rows of bottles, cups and other small ceramic and glass objects. Many visitors (including me) look in vain for one object in particular here: a big, fluted white ceramic bottle.

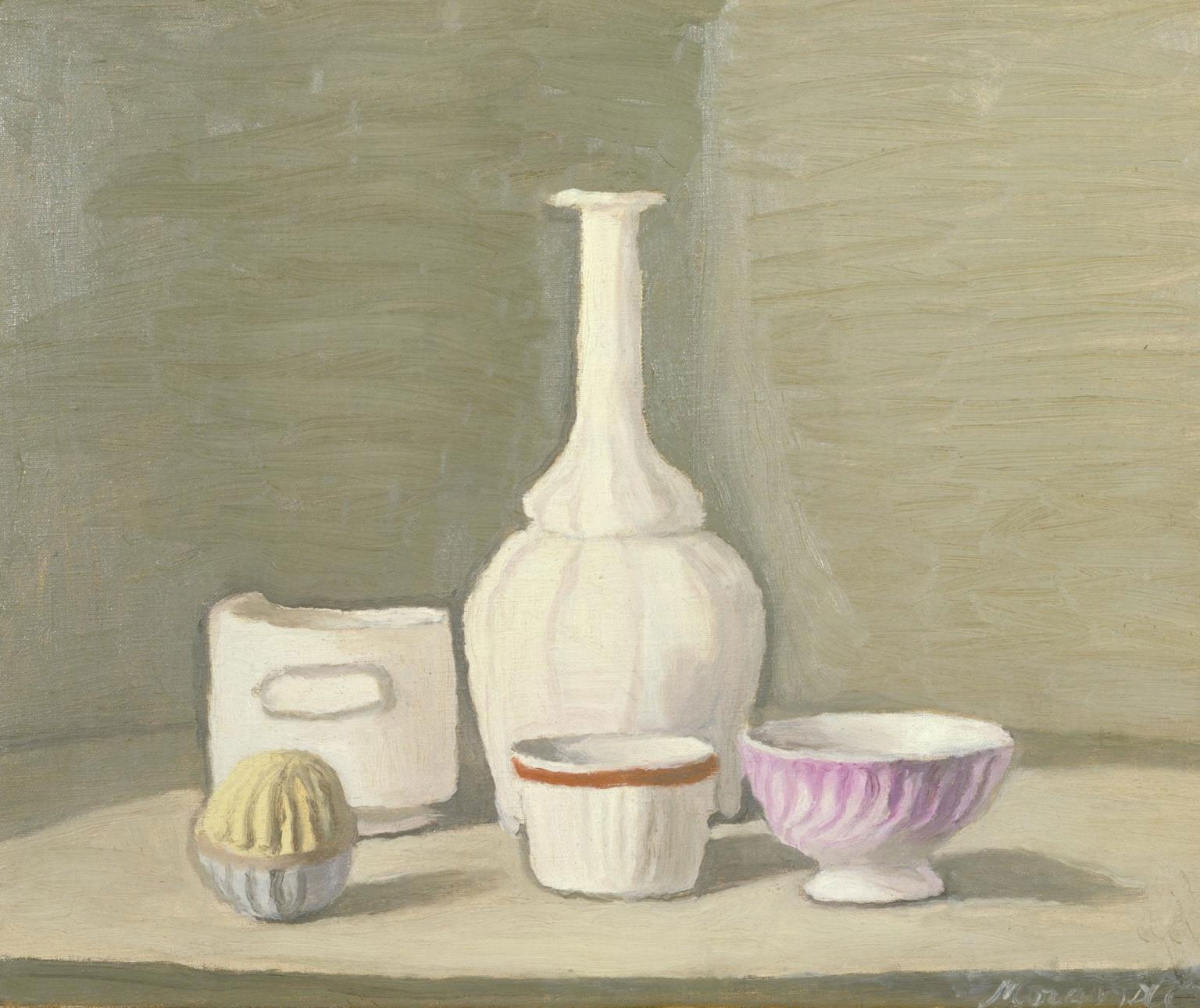

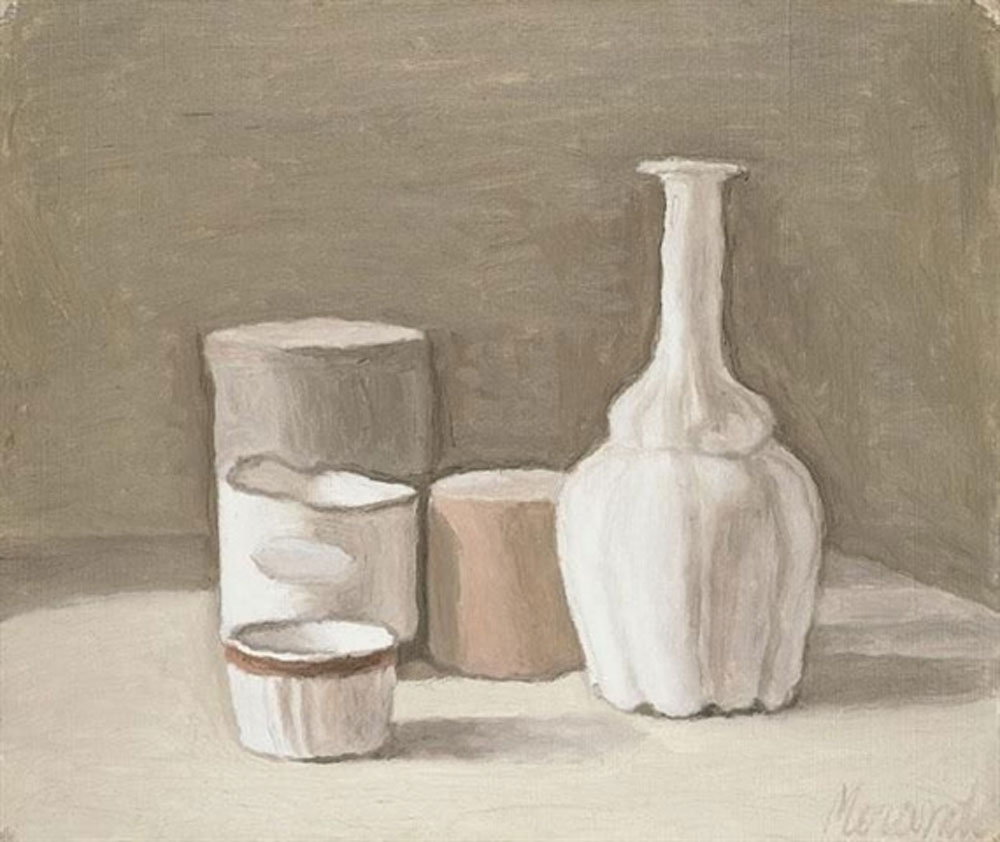

1946

1946

Morandi’s still lives mostly depict the trinkets on these shelves. Each feature a row or two of them, surrounded by a flat beige background, with the artist’s weirdly large cursive signature in a corner. The white bottle is his favourite object of all, appearing over and over again.

There’s a smaller group of works: landscapes of Grizzana, a nearby town in the hills, where Morandi had a summer home. Just like the still lives, they are very repetitive. He didn’t go outside, but painted from his window, depicting the same views. Such as the corner of a two storey building, down the hill, partly enclosed by trees.

1943

1943

Sometimes he looked out of the windows back at home in the city, too. There’s another group of paintings of the courtyard of the via Fondazza apartment.

1958

1958

All of the work shows recognisably real, normal objects and scenes. But it’s also, somehow, very alienating and strange. Maybe it’s because everything is so still and silent. Or maybe because everything is suffused with dusty, greyish, mysterious light – very different to the hard, flat light that actually shines on Bologna.

Who was Morandi? His biography, as it’s usually told, bears out his reclusive reputation. He lived in the apartment with his sisters, all his life. He rarely left it for long, except to go to Grizzana.

He fought in the First World War, but was discharged after a breakdown. In the Second World War, he lived under occupation, and painted a cold, snowy landscape from the windows of his summer home. It stands out for its bare, unadorned sadness.

1944

1944

He had a big dog called Pluto, who isn’t in any of the paintings. He wasn’t rich, and had to work at the local university. He made his own paints, and exerted rigorous control over his palette of dusty greys, reds and greens. He arranged his bottles and objects on a specially-made table that could be raised and lowered into different positions, to give him a fuller range of perspective. He died in 1964, and worked to the end.

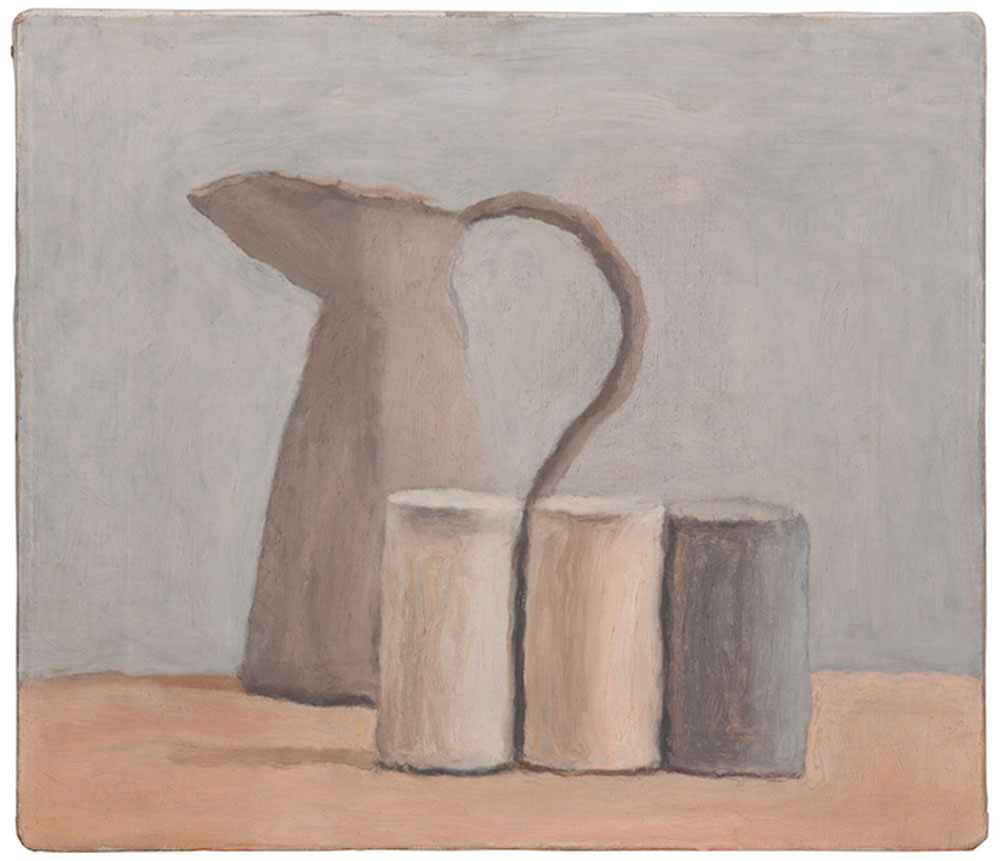

As the years progressed, the objects in the still lives became more and more monolithic. The arrangements more squared off. The bottles, jugs and pots somehow become less tangible, more abstracted, almost dissolving into the air.

1962

1962

There are almost never people in his paintings. He didn’t really deal with the human face except – very occasionally – his own. In one self-portrait, the young Morandi stares at us face-on, simply clad in waistcoat and a white shirt, the eyes dark suggestions in the beige, clay-like mass of his blank face.

1924

1924

This literal self-effacing isn’t unexpected, because Morandi treats his objects and buildings the same way. None of his bottles ever had labels. And the houses on the other side of the via Fondazza courtyard, and in Grizzana, only ever have the faintest suggestion of windows.

Taken together, the work and the life tell a story of a unknowable, remote, lonely artist – separate from the world. Hidden in his apartment, producing masterpieces.

But the work doesn’t really tell the full story of the life; and the life doesn’t explain the work. It took a trip to via Fondazza for me to finally work that out.

First, the view through the windows of the apartment isn’t recognisable from the paintings. The light is blocked by tall square blocks of flats, built in the late 50s. Browse through the exhibits, and the image of the artist-recluse recedes even further: there’s a wall of fan letters from Federico Fellini, Vittorio de Sica and Duane Michaels, among many others. Morandi undoubtedly knew he was a big deal in his own lifetime. He could have sold more paintings, and lived more comfortably. Instead, he stayed in his corner studio, and worked at the university, because he chose to.

1951

1951

While I was in the apartment, I was joined by a steady stream of fellow gawkers. A Dutch couple. An older Italian man. A group of Spanish tourists. Some stayed for a while. Some took a quick tour and left: on an itinerary, giving a few minutes to the local celebrity.

After his death, Morandi only got more famous. His influence in later 20th century art was very wide ranging. You can see it everywhere from Cy Twombly’s Polaroids of carefully-placed rows of bottles, to Wayne Thiebaud’s eerily poised paintings of cakes.

There isn’t much sign of Morandi returning to obscurity, either. There have been three separate exhibitions of his work in London this year alone. In Italy, every modern art museum I can think of has at least one of his still lives. Despite Morandi’s own (public) claim that he could only work slowly, due to the intense concentration needed to make and paint the arrangements, he was actually very prolific, knocking out as many as 70 works a year. There are well over 1,000 Morandi paintings out there in the wild – not counting his many etchings and drawings. Even the town of Grizzana has been renamed Grizzana-Morandi.

1920s

1920s

I was disappointed by Morandi’s celebrity fan letters on the museum wall, because I didn’t want to link his works of separation and silence with the fact that he lived and died as a famous man. That he had many financial opportunities, A-list friends and an appreciative public.

Which is silly of me. Morandi isn’t obscure. He isn’t a secret. He just made secretive paintings.

Visiting the apartment at via Fondazza reminded me that, while the facts of an artist’s life inform what they do, they shouldn’t shape our understanding of their work. It would be tempting to look at the apartment’s cluttered, dingy rooms and think: it was lived in by a lonely hermit, surrounded by dusty knick-knacks and uninterested in human comforts. But, looked at another way, it’s an apartment lived in by a professional, who knew what he was doing, worked quickly and didn’t have time for ornament or display.

Of course, it isn’t possible to disconnect our understanding of art from our knowledge of the people who made it. Sometimes the biography is so shocking that the art is impossible to keep separate. Eric Gill painted beautiful, lyrical female nudes … and also repeatedly molested his infant daughters. And, once you know this fact, it’s impossible to forget.

That’s not the case with Morandi, though. Even if he didn’t lead the silent, separate, hermetic life of his caricatured reputation, he didn’t lead an eventful, glamourous one either. So it’s best to put the biography aside, and focus on the work.

I found the white bottle on my last afternoon in his home city, upstairs at the contemporary art gallery – which, naturally, has a whole wing devoted to the art of its famous son. I’d thought it was ceramic, maybe porcelain. Seeing it, alone in its museum case, I realised it was actually made of glass – unevenly painted, on the outside only.

2017

2017

Morandi painted the bottle himself, in thick, uneven coats that overlap the brim. But still, glassy streaks show through underneath where the paint is thin. The final result isn’t anything special to look at. All the more so, as it was backlit by that hard, flat, un-Morandi light.

I was happy to have seen it. Because then I could turn around from the case and look back at the paintings. And realise: the white bottle lives there.