Every day in London, thousands of fingers tap a cute Kangaroo logo on their smartphone screens. As a result, every lunchtime and supper time, thousands of young men have a job to do.

They’re participating in a new, digitally-enabled form of freelance labour: working for Deliveroo, the city’s number one takeaway app. Their job is to deliver food, on motorbikes and push bikes, toting huge, insulated square food-storage backpacks, branded with Deliveroo’s turquoise and black corporate colours. Sometimes I see them riding across an intersection on the busy high street near my flat; sometimes they’re hovering around one of the street’s dozens of restaurants, waiting for their orders; sometimes they’re just hanging out with each other at the side of the road, a band of brothers. In my part of the city, Deliveroo went from nowhere to everywhere, all at once, about six months ago.

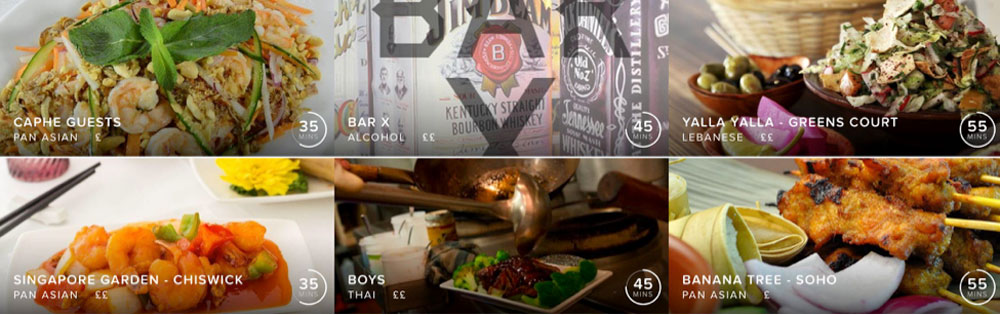

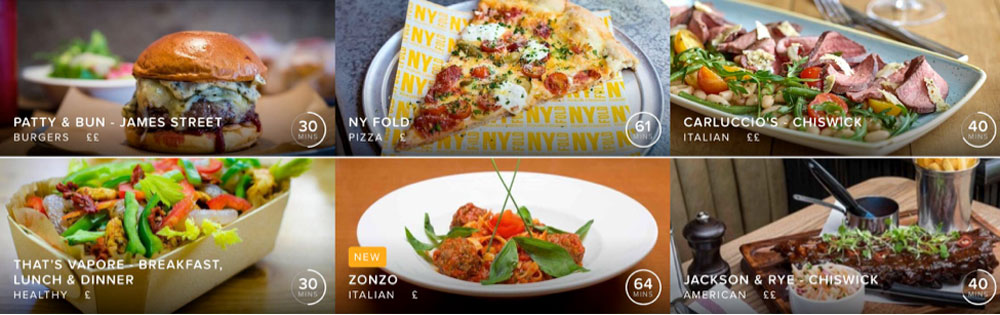

And if you’re wondering why they’re so successful, just open up the app. You’re immediately confronted with a sumptuous scrolling feed of local restaurants, ordered by proximity. It’s a Twitter for the tastebuds, a Facebook for the famished, except much more satisfying, as it delivers actual food, instead of digital Likes.

The service is more similar to Uber, actually. But, unlike the Uber app’s animated map of nearby vehicles, which gives off a coldly-efficient industrial surveillance vibe, Deliveroo’s cartoon branding, pastel colour palette and endlessly-scrolling high-definition food pictures promise sensual pleasure along with convenience. Choose your restaurant, then your meal, watch your GPS-tracked driver approach, say thanks, and eat. And it’s so easy to forget about that extra £2.50 you pay per order when no cash changes hands.

To me, it’s more than worth it. Deliveroo is a slightly more pricey, much more convenient evolution in how people fulfil an eternal and unchanging need: hunger. More than that, it’s a holy grail for the shy and the unsociable, tormented over the years by queues, cheek-by-jowl eating, the tense wait to see if your table is OK, whether or not to complain if it’s not, whether you are being rude to complain, the uncertainty over bill division and tipping, and all the other tiny frictions of a real-live restaurant visit. It also neutralises all the awkward bits of the traditional way of ordering takeaway – the stilted phone conversations when ordering, the uncertainty of whether or not to tip, and how much cash, and how far away the driver is – gone, gone, gone!

Cleverly, Deliveroo strengthens its hand among the socially uncertain with subtle snob appeal, offering food from local places too small to organise delivery services of their own, not just chains. That’s reinforced by all its thoroughly bourgeois branding and its winsome corporate vocabulary – the people on the bikes are, apparently, “Roowomen and Roomen”, according to the service’s cloying FAQ page. Occasionally, the snob appeal is made explicit: “In our platform, all restaurants have to do is cook the food, and we take it and bring it to people, which means we can work with a higher class of restaurant,” Deliveroo’s founder Will Shu, an ex-investment banker, told the BBC last year. And that £2.50 premium handily confines the service’s ubiquity to those parts of the city, office districts and affluent suburbs, that can afford it.

So far, so smug-inducing. But, just as ordering an Uber is one more handful of earth on the coffin of London’s centuries-old Cab trade, ordering Deliveroo isn’t an unambiguous gain for the city’s restaurants – or its patrons. Set up in 2012, the company has caught the eye of venture capitalists as well as the casual on-the-street observer, raising money three times last year to the tune of £66m. And my eyes weren’t deceiving me: Deliveroo really did go from nowhere to everywhere, as the business is supposedly growing at a rate of 1,000% per year, though, as a private company, Deliveroo won’t release the exact figures. Corporate backers include Facebook – raising the spectre of some future data-sharing deal: order a pizza, get followed around by pizza ads. All that investment cash helps Deliveroo compete against its takeaway rival Just Eat, fund international expansion – there are plans to spread to dozens of other cities this year – and defend its position against international rivals such as Seamless, which has a similar chokehold on posh takeaways in New York.

And what about the Roowomen and Roomen? Like Uber, Deliveroo depends on freelance manual labour, paid per delivery, with drivers often earning – according to data from Glassdoor – around £7 per hour, less than the national Minimum Wage, not to mention the city’s Living Wage. Rates are soon set to tighten further, dropping to £4.25 per delivery, though Deliveroo claims its hardest-working drivers can earn up to £12 an hour. Try living on that in London!

The Evening Standard recently gave Deliveroo its “colour feature” treatment, with one of its writers having the pleasure of being a Rooman for the day. But what was clearly originally pitched as being a light-hearted exploration of the job swiftly turned dark. The journalist-turned-Rooman was ignored, and untipped, by an endless stream of customers. After all, it’s so easy not to give any extra cash when one of the service’s intrinsic advantages is paying for everything through your phone. And the feature brought home the physical wear and tear of working for Deliveroo: the writer complained of carrying a backpack “roughly the size and shape of an Ikea bedside table” and being left “tired, hoarse, cold and starving”.

If you’re feeling particularly pretentious, you could see Deliveroo’s success as emblematic of the second machine age of the replacement of people through apps and automation, which is bound to bring about severe social dislocation. If you have a problem with the digitally-enabled tectonic societal shift away from decently-paid middle-class jobs, and towards an insecure gig economy of underpaid freelancing, then – according to this line of thinking – you should have some qualms about tapping the kangaroo.

The hammer might also be about to drop for the restaurant owners. One expert suggested in the Telegraph that vendors will feel the squeeze once the deliverer gets big enough. “Potentially the operator will look at this and think that as long as ingredient and preparation costs are covered I don’t need to sell at same price as I do in restaurant because with delivery I don’t have to worry about space or staffing costs and this is incremental revenue,” he added. Cut your margins or suffer, in other words. That is, if your margins aren’t squeezed enough by your lost business from people preferring to order your food on their phones, rather than coming in and actually paying your service charge.

Not that I’m in any position to preach. The cute cartoon kangaroo still stares out at me from the front screen of my phone, every time I unlock.

Eating’s always been a moral choice, and, for some enlightened people, moral concerns about food trump convenience and sensual gratification. To take one shining example, a century ago, after exposing the hideous cruelties of New York abattoirs in his novel ‘The Jungle’, Upton Sinclair embarked on a raw food, plant based diet, single-handedly caused the tightening of slaughterhouse regulations in the US and inspired millions to try vegetarianism.

For less virtuous people, like me, convenience and gratification reigns. I’m clued up on foody topics from the evil health-sapping qualities of sugar, to the harsh cruelty of factory-farmed meat, to, now, Deliveroo’s sketchy business model. Yet I continue to snack on jellybeans and Skittles when stressed out. I eat meat bought at the supermarket. And, from time to time, I tap the kangaroo and order some takeaway through my phone.

The last time I ordered with Deliveroo wasn’t long ago. And, having been researching this article, I was well aware of the moral dubiousness of my choice. It had been a more difficult day than usual. Nothing major, just a struggle at work, followed by an aborted trip to a ludicrously packed restaurant and a silent bus ride home. But it was enough. Half an hour later, an excellent burger was at the door. Patty & Bun in London Fields, if you want to know. (Is it nice there? I’ve never been.) I didn’t tip, either. The Rooman rolled away, onto his next £4.25 delivery.