I stumbled on today’s People’s Vote march by accident. Totally done in by the endless Brexit news cycle, having pinwheeled over the months and years since the referendum between hope and disillusionment, I’ve recently taken the coward’s way out: avoiding Twitter updates and news in general on the topic.

This meant that I vaguely knew about today’s parliamentary vote and the march, but this vagueness was sufficient for me to plan a Saturday afternoon trip to some West End galleries, which involved getting out at Green Park station. A station which was of course right next to the march’s route. I should have guessed from the crowd on my tube journey, up from the furthest-flung, poshest, whitest branch of the western District Line.

The train was rammed with families and groups of pensioners, clad in European Union flags, home made signs in their hands. And by the time I’d passed the station gate line, I realised that making it north of Piccadilly, where most of the galleries are, would be impossible.

Shuffling into the park, I got more of a measure of the march’s demographic. Two word summary: well heeled.

I saw one woman in the octagonal Ace & Tate eyeglasses that seem to have taken over London this autumn, clad in a t-shirt: ULTRA REMAINER. Another couple, the man in a waxy Barbour jacket, holding a sign pleading to stay in the EU for their grandchildren, whose names included “Theodora” and “Felix”. There were several cute dogs clad in EU flag coats - or sometimes sporting the bright yellow BOLLOCKS TO BREXIT sticker I’ve seen so many times recently.

I let go of my gallery plans, and decided to march instead. One of the exhibitions on my list I’d been blocked from was a Luigi Ghirri show at Thomas Dane Gallery. It’s based around Colazione sul l’herba, the Italian photographer’s star-making series from the early 70s, in which he depicted sunny, well-ordered scenes from Modena, his prosperous hometown. He was in his element in peaceful suburbs full of wealthy people - just the type of place most of these marchers are coming from.

Some ultra-wealthy, too. I could have sworn I heard a champagne cork pop, up on a balcony in one of those incredibly grand houses that overlook the eastern edge of Green Park. That’s St James’s, home of hedge funds, gentlemen’s clubs and the kind of galleries that are private-appointment-only on Saturdays. And… it looked like a People’s Vote party, with one of the (white, middle-aged) people sunning themselves on the balcony wearing a felt EU flag hat.

In the orderly queue for nice sandwiches from the Green Park food stand, a Gen Xer wore a black T shirt with the yellow Nirvana font, with a single word: REMAIN. “It’s all very chilled actually,” an arty type trilled, into her iPhone.

Walking down towards the Mall, I overheard the concerns of advanced age: “Excuse me, are there steps at the end there?” And felt the enormous Englishness of this crowd. Among the few people from other European nations I saw was a confused family of Spanish tourists, walking contraflow, presumably wondering why their trip to see Buckingham Palace was being disrupted by these genteel hordes. Also working in the garden one of the grand houses was a builder in a high viz gilet, alone, back turned to the march. As good a likelihood as not that he was here from Eastern Europe.

I remembered the other People’s Vote march I’d attended, though at that time I’d been much more furiously engaged in the Brexit ups and downs, and had specifically planned to march. I had to check my phone for the date: 20th October 2018. I have no memory of at which turn in the negotiations this event took place, but I remember a similar demographic of marchers - and a similarly sunny day.

I overheard a kid’s voice, shouting “bollocks to Brexit”. I heard a whistle following the same syllabic rhythm of these words over and over on the march. I knew which words matched the rhythm. Bollocks to Brexit - it’s gone beyond words, beyond a political strategy. It doesn’t relate to any future referendum. I’d argue it has gone beyond revoking article 50. It’s an incantation, the aural equivalent of an #FBPE hashtag on Twitter. It’s taken deep root in the brains of these people, and it’s going to inform their political decisions for decades. Mine, too, probably.

Just like the 2018 march, it was surprisingly quiet. There were some group chants, taken up sporadically, but nothing really getting going. No collective shouting. Having had comparatively little to protest about previously, these aren’t experienced protesters. A few choruses of Ode to Joy, nobody really knowing the words, just the tune. And probably being too embarrassed to sing along anyway.

On Pall Mall, I joined the march properly, behind a little forest of signs for REIGATE LIBERAL DEMOCRATS. There were a lot of children excitedly marching with their families.

My mind wandered. I’d attended, and written about, the Ghirri retrospective at the Jeu de Paume a few months ago. Something in me responded to the comfort and hopefulness of his photos. His well-swept patios, tidy hedges and stacks of consumer goods are lit by golden sunlight and undergirded by solid years of post-war economic growth. Ghirri, a surveyor by trade, delighted in an almost mathematical precision in his depictions of bourgeois life. Along with the beauty of his images, there’s an easy acceptance of the movements of capital that built his world; one of his favourite subjects was advertising billboards, which he photographed obsessively. What made all this wealth? Italy’s membership of the European Union since the 50s was one factor.

At the bottom of Haymarket, I took a little break. Looking up towards Piccadilly Circus, life carried on as normal, a double decker bus rounding the corner and going up the hill, I looked back at the ugly, pompous Crimean War memorial at the intersection with Pall Mall, and the passing marchers. The photo above was soundtracked by a fellow spectator, a man in work overalls, who I guess had had his way blocked by the march. He said to his colleague: “I think it’d be easier if we drove a van through them.”

Despite being definitely more on the side of the people getting run over by the van than the driver of the van, I felt too ambivalent to risk the crush down Whitehall, so I bailed from the march at Trafalgar Square: pretty much the point where I’d joined the previous one in 2018.

Walking back towards Embankment, I saw one of those bike rickshaws, with two confused Indian passengers, on a doomed mission towards Leicester Square, I guess. Blocked by the huge crowds, the rickshaw came back without the passengers two minutes later.

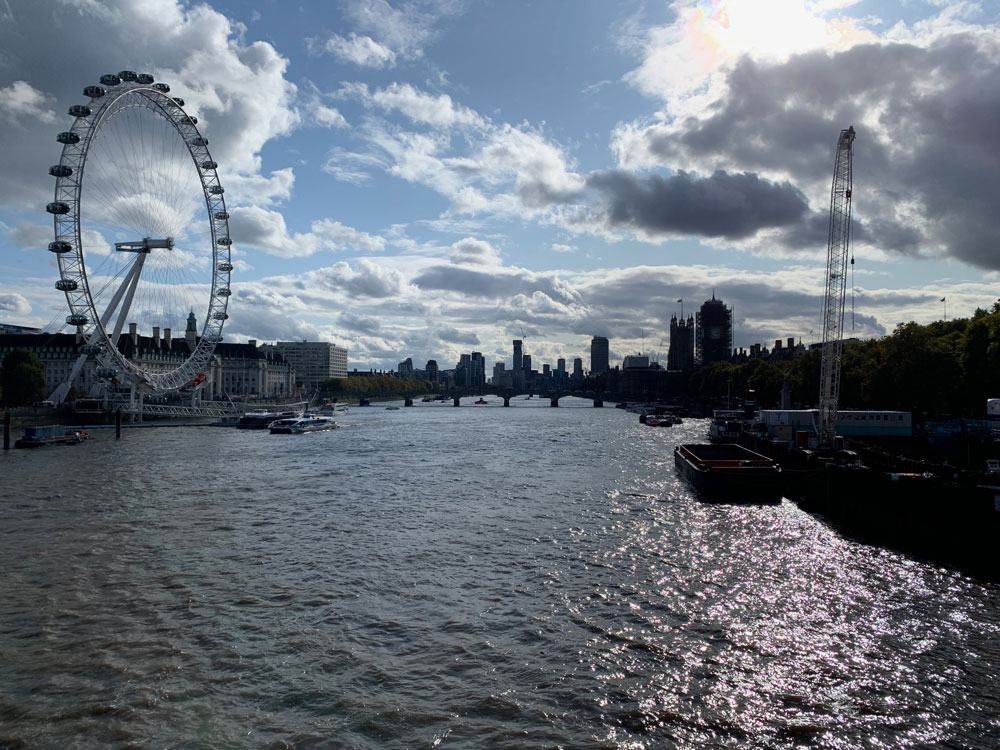

Crossing the river via Hungerford footbridge, I was still in a crowd, but this time a far more ethnically and nationally diverse one of tourists. I looked upriver: close by, the Millennium Wheel, icon of a more hopeful recent past, further away, the new Dubai-style towers of Nine Elms, and on the other bank of the river, parliament, where the Brexit wrangles continued.

Then finally, I drafted this post in the Southbank Centre, as news came through of the government’s latest parliamentary defeat, staving off the final Brexit agreement for a couple more days at least. I felt my patience being stretched by the braying hordes of marchers, loudly comparing notes as they ate and drank in the atrium.

I took a mournful look at Thomas Dane’s website, making plans to see the Ghirri show next week. Where’s his Italy now? Where’s the UK? My fellow marchers have experienced so much bourgeois ease, but they now realise they live in a world of angry people on the sidelines who’d quite like to drive a van through them all.

And I’m sure this anger is returned, despite the placid nature of the march. I saw an impeccably middle class kid, no more than eight years old, with a cardboard sign saying FUCK THIS in rainbow letters. His parents, no doubt, share the sentiment.

Here’s another picture from this afternoon. I overheard a dad and son, taking a break before going down Whitehall, discussing the flags and the slogans in the clipped, awkward, embarrassed way of the British middle classes.

I’m being snide. I saw myself in both men. I realised that my reactions to my fellow marchers are rooted in my own self-doubt. That in seeing them, I’m seeing myself. And I’m wondering what I’m looking at.

Maybe it’s best to look at something else. Some photos of sunny days from an increasingly distant past. The Ghirri show runs until November 16th. Pre or post Brexit? Who knows?