“What we are seeing today is a backwash from what happened 10 years ago.”

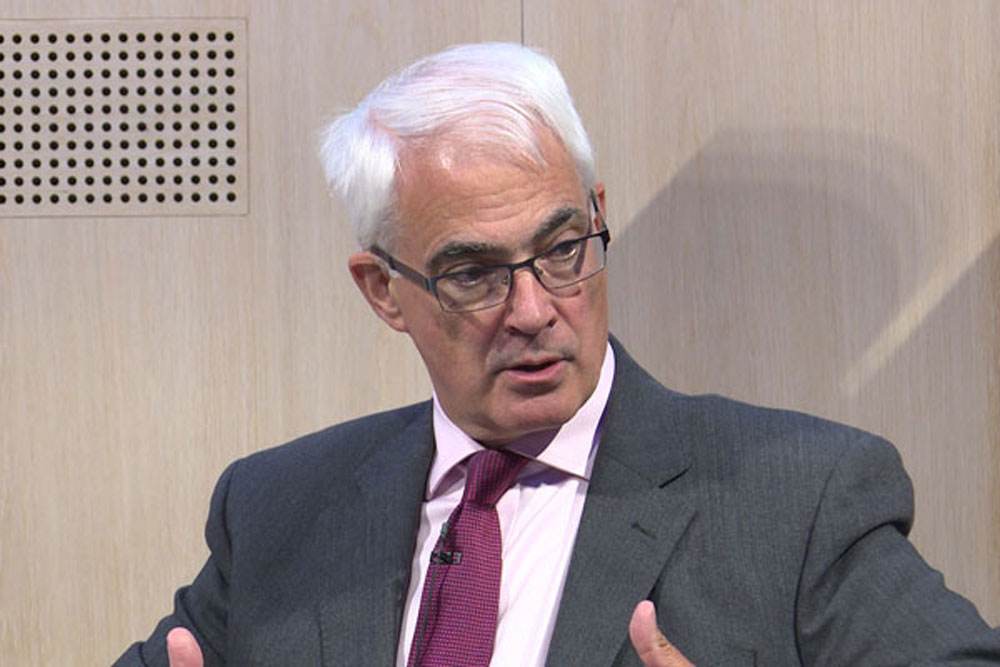

So claimed former Chancellor of the Exchequer, Alistair Darling, in an event organised by the RSA and held in London a couple of months ago. Darling was in charge of the nation’s finances when the biggest financial crisis in a generation hit in 2007. He articulated a view that has been forming with the recent political ructions and rise of populism. The crisis, for him, led to “political developments, culminating, in our age, with Brexit, and in the US, with Trump”.

Prior to 2007, Britain enjoyed “Wild West” days, of easy credit and exotic financial instruments. Interest-only mortgages, that many borrowers had no hope of repaying, were eagerly offered by margin hungry banks, then repackaged and resold to other institutions. Even the smartest commentators found their brains fried in the frenzy: see this unbelievable-to-read-these-days article from Michael Lewis, from early 2007.

Then, when the crisis hit, many were pitched out of their homes. And Britain suffered its first bank run in 100 years, with the collapse of Northern Rock. (Several other big financial institutions, from RBS to Lloyds, were also taken into public ownership before the crisis was done).

Alistair Darling

Alistair Darling

While we are apparently dealing with the political consequences of the crisis – more on that later – the actual vertiginous feeling of those crisis days, particularly when the eye of the storm passed in the autumn of 2008, has been quickly forgotten.

Including by me. Like everyone else, I felt the crisis when it happened. I didn’t have a home to lose, as I was scraping a living as an underpaid and overworked financial journalist. I did temporarily lose my ultra-high-interest savings in Icesave, one of the most infamously badly run financial organisations of the lot – before the government paid it back. And, when Lehman Brothers failed in September 2008, I was working nearby. That grey morning, I trooped over to their skyscraper headquarters on Bank Street in Canary Wharf, and watched a trickle of sharp-suited men carrying archive boxes of their stuff out of the building, out of a job. Plus a thicker crowd of my fellow journalists taking their picture.

A month later, the eye of the storm crossed the Atlantic, and RBS – one of the UK’s largest banks, which had dabbled in the exotic financial instruments with particular fervour – went down.

On the morning of October 8th, Darling received a phone call that “sent a shiver down my spine,” he told the audience. Down the line was the head of RBS, telling him the bank was “haemorrhaging money,” adding: “We are going to run out this afternooon.” That’d be one of the biggest banks in the UK going down: what was ultimately a sharp recession could have taken down the global economy.

I remember having drinks in London after work later that day (my 26th birthday). Leaning against one of the solid stone columns round the back of the old Regent Palace Hotel in Piccadilly Circus, and wondering (over-dramatically) if the civilised city scene would still even exist in a year’s time. What would happen? Packs of wild dogs marauding the streets? A post-apocalyptic streetscape of smoking buildings? People who would otherwise have been shopping in Hamleys foraging for food instead? Such silly ideas seemed credible – not least because I’d spent the day reading frightening statements and investment notes from the very banks that were themselves in imminent danger of collapse.

It wasn’t very reassuring to hear that Darling was thinking similarly dark thoughts. “It was an absolutely seismic event – we were that close to the brink,” he said. “After, I thought it was like a nuclear missile crisis.” And his own government, with its benign view of loose credit, was partly to blame. “Governments wanted the population to be happy. Happiness was owning your own house.” Which led to lax regulation and complacency.

Many now question the government’s decision to take RBS over. And bemoan the fact that the bankers who dealt in these exotic financial instruments didn’t go to prison. “Bad judgment is difficult to criminalise. Moral hazard is a great concept. But not when you’re firefighting, and faced with imminent collapse,” Darling argued.

“One thing that government must avoid is panic. People losing confidence in institutions. If RBS had gone down, taking everything with it, the bankers wouldn’t have suffered. Ordinary people would have suffered.”

This simmering sense of injustice seems to have found expression in the recent wave of populism. “The bit that depresses me is what happened after [the crisis]. I didn’t think 10 years ago that we would still be living with the consequences. But we are.”

These consequences are both economic and political. “People are turning to things that will make things far worse,” said Darling. “Where globalisation went wrong is that there was not enough attention paid to those who lost their jobs.”

As if that wasn’t depressing enough, Darling wound up by predicting another crisis to come. After all, if there is a recession now, what levers do we in the UK have? Zero interest rates (though the Bank of England has recently increased them, marginally), dire productivity, and an economy running on fumes. That’s before we think about the Brexit bill coming due.

“The thing about crises is that you don’t know where they will come from.” Generational injustice is one possible source. “You are working to pay off your student debts,” he told the few members of the audience who were much younger than him. “You are also paying for my pension.”

Though there are some blessings to be counted. The same Regent’s Hotel that was the scene of my existential freakout a decade ago is still standing. The packs of maurading dogs seem far away.

London gleams. In fact, the hotel has been renovated, ‘deathmasked’, clad in hideous green stone, with some tourist friendly shops and a Whole Foods around its base. Even the seismic impact of the financial crisis, and the shock of Brexit, didn’t stop that happening.