I read less than I used to, and I forget most of what I read. A fact brought home to me last year when, bored at Christmas time, back at my parents’ house, I rifled through some shelves in my childhood bedroom, and pulled out a plain blue hardcover notebook.

I’d found an old reading journal, each line of the notebook had a ‘date begun’ and a ‘date finished’ for each book I read. It was from 2005: the year I finished my MA, when I lived in a tiny flat in Bristol with no TV or internet connection, and took a long train journey to another town most days. All of which led to me reading a lot of books, according to these notes. At least two knocked off per week, sometimes four. But I forgot almost everything about these 100+ titles, beyond the odd stray scene, phrase or feeling. And, now, a collection of dates.

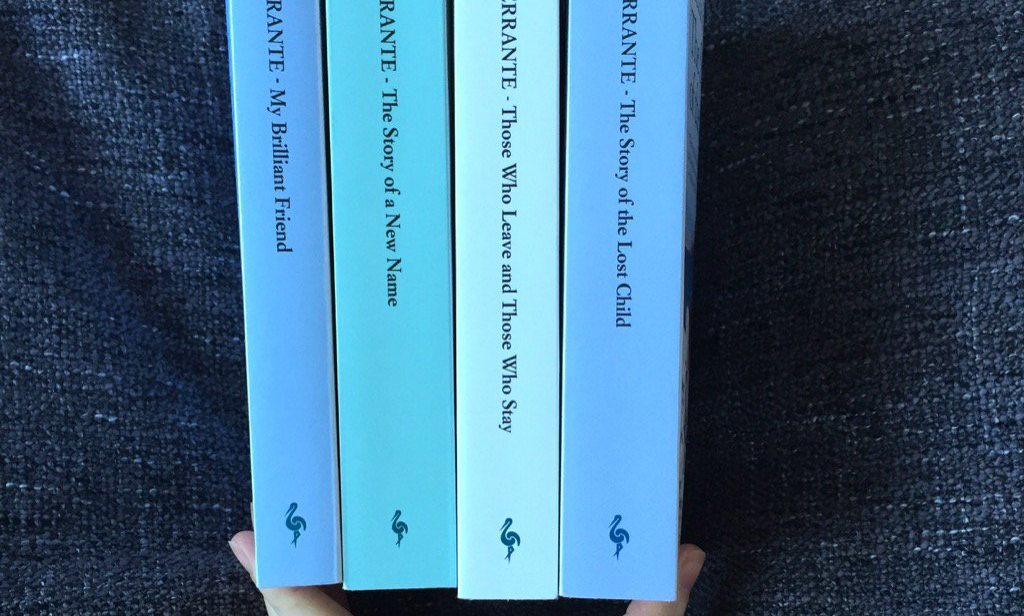

Anyway, no hope of that summer coming back. 10 years later, working longer hours, commuting by bike and constantly checking my smartphone or computer. According to my Google Doc – yep, still taking notes as I read, just not on paper – my annual total has dwindled to the 24 titles listed below for 2015. 21, if you count Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels as a single work. And, in an effort to remember more about them beyond dates started and dates finished, here’s what I thought.

The best books I read last year…

The best books I read last year…

First up was The New New Thing, Michael Lewis’ account of the first dotcom bubble. I came to this one through a long-held Lewis love. I particularly love his lightly worn, though relentlessly-clever, journalistic craft: from his breakthrough Liars’ Poker, to How I Got Into College, one of the most riveting of all This American Life’s thousands of stories. This time around, I savoured Lewis’ customary sly skewering of a super-rich subject (Netscape founder Jim Clark), who was in the throes of a quixotic and doomed attempt to reform US healthcare from the back of his superyacht. The book’s flip, seen-it-all authorial voice worked a lot better than it did in The Big Short, where all that jokeyness wore a bit thin when the consequences of his story led to economic ruin for millions of the type of people Lewis wouldn’t dream of having to dinner.

A lot of last year’s reading was thin books on topics I know nothing about. Included in that group is The Qur’an: A Biography, by Bruce Lawrence, which I apparently read in February but can remember nothing about. Much more memorable was Cheryl Strayed’s Wild, a hippy quest with an amazingly empathetic and stridently original new author’s voice. (Her Longform podcast episode is also really rewarding.)

Having never spent so much as a night in a tent I’d never fantasise about hiking and camping across the Pacific Northwest. But I’d definitely fantasise about renting a flat in the Barri Gotic for 300 euros a month: that’s what Colm Tobin did in the late 70s, anyway, according to Homage to Barcelona. If Toibin is occasionally a bit smug and studied he’s still an awesomely accomplished portraitist, and the short book is obviously speaking from a place of love.

There’s much less affection in ‘The Yacoubian Building‘ by Alaa al-Aswany, which I read after watching the (brilliant) film and my first novel of the year. A very remote culture from that of Barcelona, and my own, and so I learned a lot. The most memorable example here being the social strata of posh, francophile Egyptians cast aside by the Nasser revolution, yet still hanging on grimly to much of the nation’s cash. Among which was the book’s most memorable character: the terrifying Dawlat, the aged hero’s scheming sister.

Reading back, there’s a big Mediterranean theme to my book choices for the year: Italian Ways, by Tim Parks, looked into what the nation’s trains say about its people. Mainly, they seem to say that the Italians are a lot more civilised than the Brits, a fact that occurred to me once more when I took a real-life Italian train later in the year, and was bowled over by its cleanliness, stupendous cheapness, Siberian air conditioning and the sweetly officious conductor who checked my ticket with his hip-mounted iPad. I was very far from home.

A much more excruciating Italian adventure is described in ‘Days of Abandonment‘, in which Elena Ferrante gets dumped, goes crazy, kills (sort of) the family dog and prostitutes herself to the downstairs neighbour in the most embarrassing sex scene I’ve ever read. What could be melodrama in less sure hands became totally riveting. I finished it in a couple of lunch hours, hands shaking for parts of its second half.

Back to Britain in ‘Excluded from the Cemetary‘, a now out-of-print British sci-fi novel of the 1960s lent to me by a friend. His favourite book. The author, Peter Marshall, only wrote two. The atmosphere of dread and alienation just has to have been from life: Marshall apparently spent his, once confined to his wheelchair, in near-isolation. Which contrasts with the obviously super-social Edmund White, whose ‘Inside a Pearl‘ suggests that he’s Paris’ most cosseted resident since Marie Antoinette. While White’s total solipsism ground my gears, I also found this gossipy book totally addictive. Though, as with all White’s work, it came to a sad end: he can’t escape his own feelings of worthlessness and estrangement from the friends and lovers he courts so avidly.

Really liked; quite liked; absolutely hated

Really liked; quite liked; absolutely hated

Another indiscreet old queen’s memoirs, ‘Almost Always, Never Quite,’ came next. The late art critic Brian Sewell’s childhood memoir was more self-aware, but less self-critical than his sister across the channel. In fact, Sewell’s total honesty at the end of his life (the author bio on the inside flap claims him “as old as Methuseleh and as frail as the stricken Job”) makes him a great autobiographer. I’m reading volume two in 2016.

Back across the channel for ‘The French Intifada‘ (Andrew Hussey), going out into the Parisian suburbs that White barely mentions and never treads, to tell the story of French colonial history in the maghreb; as in his previous biography of Paris, Hussey’s authoritative and a bit laddy, though his musings on the purported alien nature of France’s Arabs earned him a thorough kicking in the Guardian and on ‘Night Waves’.

I miss Lynn Barber’s vicious interviews since she disappeared behind the Times paywall, so I wolfed down ‘A Curious Career‘, a lightly padded interview compilation, including her hate-at-first-sight run-in with Rafael Nadal. ‘What a Carve Up!’ by Jonathan Coe was a funny compendium of Thatcherite grotesques from a determined left position, though the final 100 page diversion into Hammer Horror sits oddly with the rest of the novel.

In ‘Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste‘, bought as a birthday present – so read rapidly on a strict deadline – a deeply earnest music critic (Carl Wilson) discusses bad taste via Celine. I wish there’d been more discussion of her rather than his struggle with taste – maybe the sign of a genuine double-A lister is that they don’t reveal much about their lives? – but still really fun to read. If that short work was a surprise pleasure, ‘The Children Act’ by Ian McEwan was pretty much exactly what I expected. At a sentence level, there’s nobody better. But, having originally written about the comfortable middle classes in the 1980s, he’s drifted upwards to covering only the super-elites these days. And there was something unseemly in the way the less worldly and their troubles are shifted away to suffer and die, away from the socially secure and financially advantaged protagonist, by the end.

But at least it’s quiet privilege. Raging entitlement screams from every page of ‘Portrait of an Addict as a Young Man‘, in which Bill Clegg offers the memoirs of the worst boyfriend ever; narcissistic and charmless and loving every minute, then glorifying in his own ‘brutal honesty’ as justification of his own appalling behaviour. In a book with so much purported pain, the reader gets no sense of suffering. Nastily, I wanted him to suffer more.

Prior to my one long holiday of the year, in Portugal, I started ‘Alentejo Blue‘ by Monica Ali. Not being able to get into it while I was actually in the Alentejo, I finished it in November: it’s very slight and episodic, a chain of linked short stories set in a small Portuguese village; Ali’s English characters are definitely more surely handled but moments of great insight and scene-setting skill throughout. It all culminates in a party, unlike the misery-soaked ‘The Gates of Damascus‘ (Lieve Joris), a tale of a claustrophobic encounter with a Syrian woman, daughter, family and husband in jail in the early 1990s. If features a hard-to-read trip to Aleppo, described as a centre for cosmopolitanism and free-thinking compared to stuffy old Damascus. Little did they know. Googling the characters after I was done revealed Joris’ friend curdled into fundamentalism, stuck with her daughter in a Dubai high-rise. At least she escaped.

Two more art books went down like ice cream by comparison: the big revelation of ‘Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling‘ by Ross King was that the Sistine Chapel wasn’t painted with the artist flat on his back, nose inches from the fresco, swinging from the scaffold: contrary to that long-standing myth, he was in fact standing up and leaning back, with no greater discomfort than a sore neck. And ‘Black Vinyl, White Powder‘ by Simon Napier-Bell, a history of British music in the context of drugs, told in anecdote, was pop art of a different kind. Its really entertaining writing more than makes up for the author’s (understandable) generalisations and sketchiness, though all of the approving quotes from Jimmy Savile and Jonathan King seemed a bit suspect. (The book was published in 2000.)

The best for last: I binged on Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels over Christmas, by the last book not even being able to wait for the Amazon order, and picking it up for full price at the bookshop so I could start it right away. Amazingly addictive and satisfying, it’s almost miraculous the compression of action and feeling Ferrante packed into each paragraph.

But, unavoidably, the finer plot details are already slipping away, a couple of months on. As will whatever I manage to read this year. Hopefully there’ll be a few more novels, and a couple more classics, in 2016.