I spend around 10 minutes a day on Duolingo and I’m not convinced it’s worth it.

And the fact these doubts only started occurring to me after I completed a 100 day streak on this maddeningly well-designed and moreish app is… annoying.

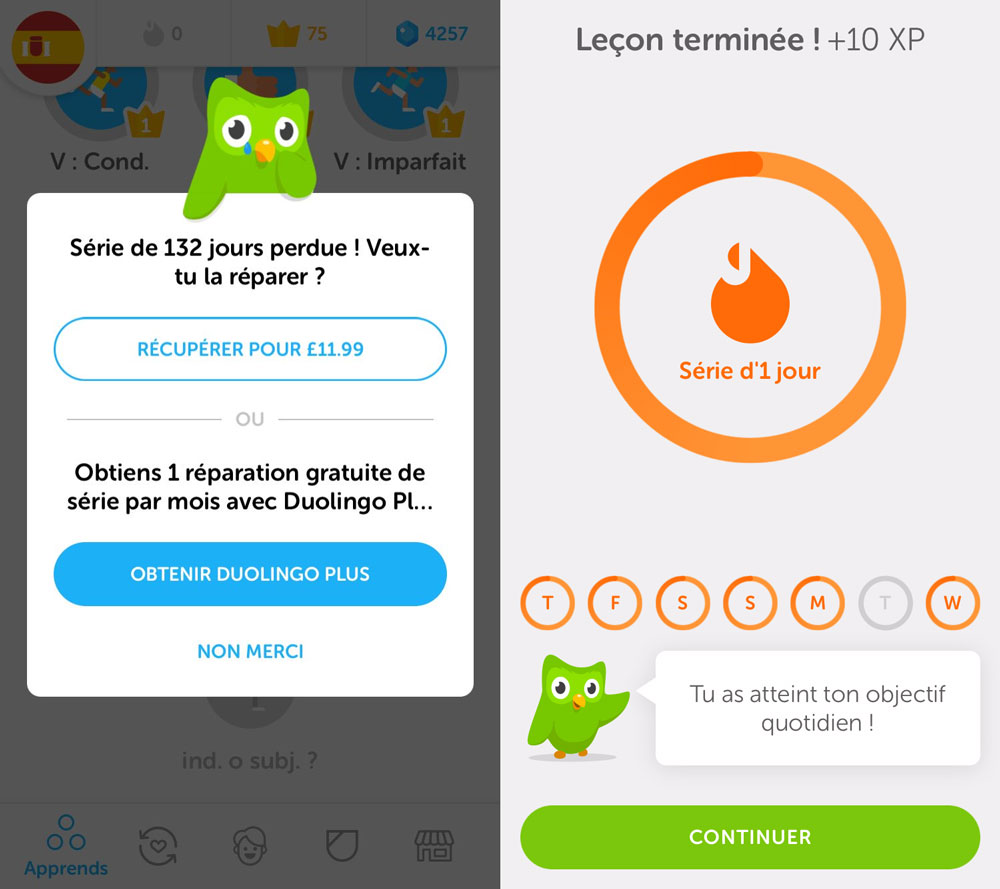

Admittedly, 10 minutes a day isn’t a massive time commitment. But, over 100 days, that equals almost 17 hours. Most of a day! Is it even time well spent? I guess ‘yes’ was my subconscious answer, because I went all the way to 132 days before breaking the streak…

The daily ritual is always the same. I complete two units in total, the bare minimum necessary to maintain the streak, in one of three languages: Italian, Spanish and Portuguese, all of which I feel like a rank beginner in. All three translate into French rather than English, so the biggest gain in theory is there. (I got that idea from a fellow addict, as improving my mediocre-to-intermediate French is my number one language goal.)

Aside from the outlandishly long daily streak, I’m representative of the typical user in terms of daily time spent in the app: according to Duolingo’s own internal stats, 10 minute sessions are absolutely average. Also, the fact I use the app in the first place isn’t that unusual: it has around 150m users overall, including 25m monthly actives. Duolingo offers more than 60 courses in 19 languages in total. Unsurprisingly, slightly more than half (53%) of Duolingo-ers use it to learn English.

Not that all that usage is strictly functional, though. There’s a smug good-citizen buzz in using a purportedly educational app. Spending time on Duolingo feels morally superior to spending time with one of the self-esteem destroyers lurking elsewhere on my phone’s home screen: looking at you, Instagram!

And it’s fun to ‘learn’. The UX is vastly superior to rivals like Memrise, hooking you in through its bitesize lessons. The tasks are satisfyingly varied: from selecting pairs of words, speaking into the microphone, to building sentences through tapping word-cards.

Its design is adorable, with its owl mascot, and the cute cartoon characters giving the tests (including a gay couple with matching woolly hats, a zombie and a dolphin). And it gets the little things spot on too: a right answer results in a satisfying ba-bing, a mistake a disappointing tap-tap. Sometimes, getting into the flow of question and response, stabbing the keyboard faster and faster, piling up the ba-bings, this user feels like a linguistic virtuoso.

All that language learning is unsurprisingly lucrative: Duolingo has been valued at $700m, and is preparing to go public in the next couple of years.

Invented by Luis Von Ahn (already mega-rich after co-inventing the now-ubiquitous website security tool Recaptcha and selling the technology to Google), Duolingo was originally conceived as a project where people learned languages, and also helped to translate content on the web. It worked by pulling content from web pages written in the user’s learning language, which the user then attempted to translate. When enough users – at different levels – had had a go, the true translation was added to the foreign language web page.

That was the idea, anyway. But improving online translation services, thanks to machine learning, meant that Duolingo quietly turned this feature off over a year ago, albeit to howls of protest from hardcore users.

Not that such a worthy idea would have got Duolingo a $700m valuation, anyway. Instead, it’s basically an ad play these days. And the app’s monetisation strategy is typically brilliant. Duolingo has never done any paid advertising itself – it spread the word through very positive media coverage. The content of the ads shown to users is currently dreadful: obnoxious 30 second videos with impossible-to-ignore music, for crappy-looking mobile games. But the evil genius is that users are incentivised to watch them, as watching them rewards them with extra lingots: the in-game currency that can be spent on features such as bonus levels. Or, even more pertinently, it restores some life force to maintain that all-important daily streak. Basically, it insures that freeloaders like me watch the ads. (Duolingo also has a paid-for tier that feels like a total afterthought.)

The incentive to watch them is going to get even deeper in future, according to Von Ahn. He said the ads are going to become ads in the language the user is learning. Genius. Us learners will watch them extra-closely, and Duolingo can go back to their advertisers with sky-high engagement scores, and up their prices. Everyone wins, right?

That’s not to say the service is perfect. The store in which the user can spend their gems is full of stuff I have no idea about and don’t want to purchase – I only want gems so I can keep my streak going if I make too many mistakes! (It costs 450 lingots to refill a user’s strength after running out – five mistakes are allowed per day in total.) There’s a baffling system of badges. The sign-in to the service is through Facebook, but the social element to the app is a little-used add-on that mainly lives on duolingo.com.

And where has my hardcore fandom actually got me? To return to my original question from a different angle: am I actually better at French 100 days of Duolingo later? I’m certainly not any better at Portuguese, Spanish or Italian, none of which I’d attempt at anything other than the most basic level.

How about French then? I had the opportunity to test it out on a trip to Bordeaux a couple of weeks back. And my French was pretty much as passably mediocre as before. I felt my vocabulary had improved. I could spend money (food, drink, tickets) slightly more fluently. But any deeper conversation and I was floundering as if I’d just been cast into the river Garonne in deepest February with no life jacket. So, spending the bare minimum time on a language learning app for many days in a row doesn’t make you a master in the language you’re learning: here ends the social science experiment.

Anyway, I was so busy ordering drinks and food and tickets in French that, on day 133, my streak came to a sad end. Unsurprisingly, Duolingo’s evil genius at monetisation meant that they set an extra-but-not-stratospherically-high price to maintain the streak (£12). To my shame, I was seriously tempted to spend it, before returning to my senses… and a 0 day streak.

Despite having kept my credit card in its virtual wallet, I kept on going with the app. I’ve travelled so deeply into Duolingo’s cutesy world of owls, dolphins, and ba-bings that I’m not even sure I can leave.

I wonder if another 100 days there will actually make me better at speaking foreign languages?